Thanks for following our blog. Our goal is to provide you with the most recent information about our business and landslide related issues and initiatives in Western North Carolina. So stay tuned in, especially when we get a lot of rain!.

The 1847 debris flow event in Clay County, North Carolina shows crazy storms aren’t a new thing for the region

Seeing the results of past extreme storms in a region is an important part of understanding potential landscape behavior. Thomas L. Clingman (yes, that Clingman) provides an invaluable record of a couple of past storm events in his extensive writings about western North Carolina. His discussion of the results of a storm of July 7th, 1847, in Clay County is particularly interesting. The document is linked here, but the excerpt below contains the important parts found on page 76 of the document. Anyone that saw the effects of a Helene debris flow will quickly recognize exactly what Silas McDowell described to Clingman.

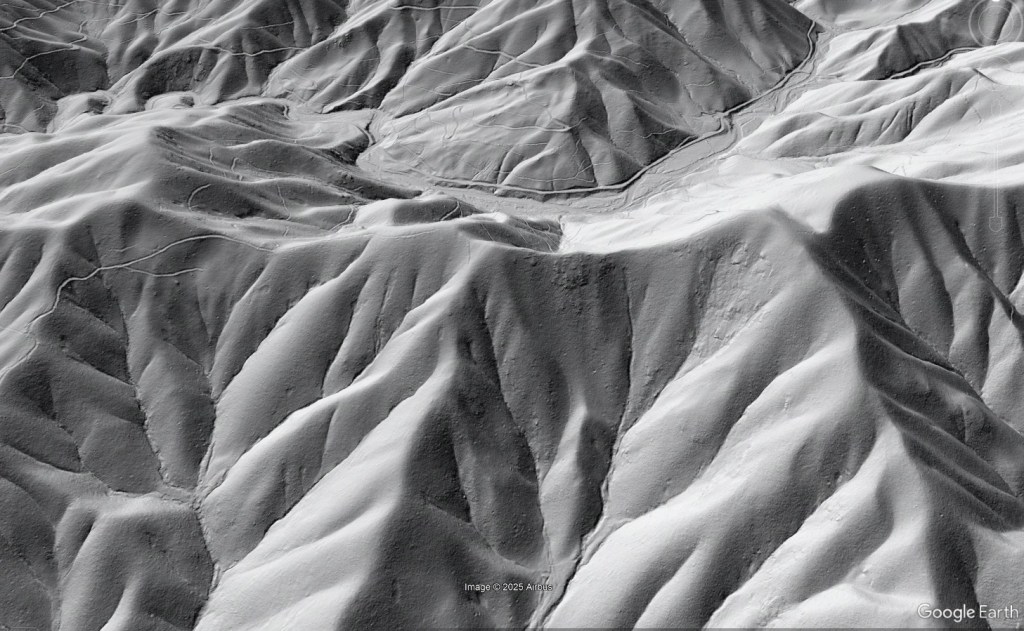

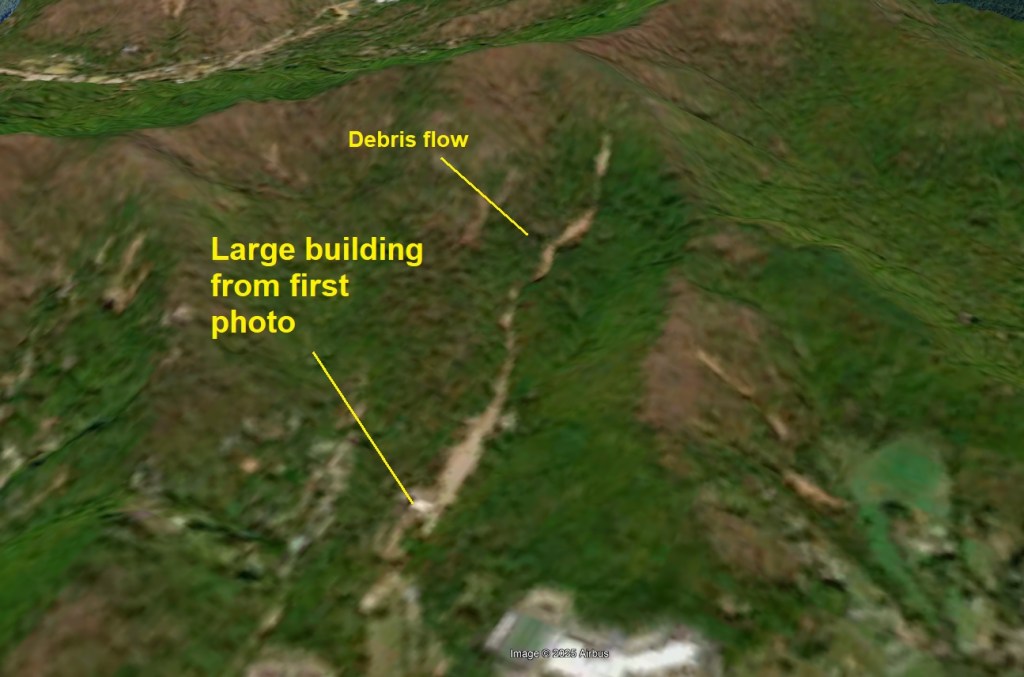

McDowell was very clearly describing debris flows to Clingman (not “waterspouts” as we use the term today), and Fires Creek Mountain was obviously hit with an impressive cluster of them during this storm. Because debris flows visibly scar the landscape, could a geologist still see the effects of the storm on Fires Creek Mountain nearly 180 years later? I took a stab at this a few months ago, and I was impressed at how well the combination of Clingman’s notes and 21st century lidar imagery worked together.

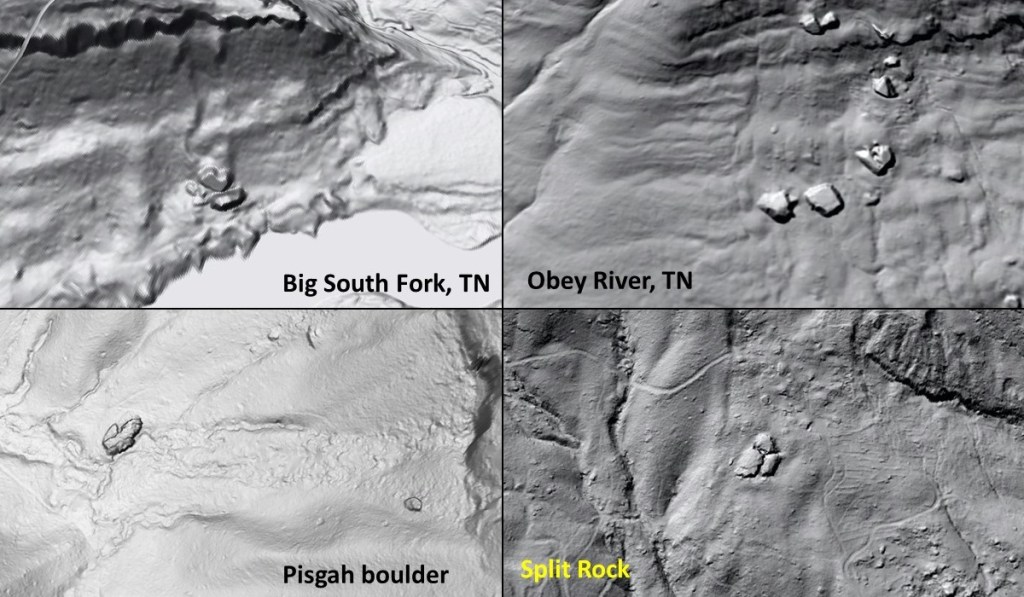

If you want to go looking for 180 year old debris flows, you need to know what sort of scars you might be looking for on mountainsides. An effective way to do this is to examine the lidar-visible scars of known debris flow events. The November 1977 storm produced quite a few debris flows southwest of Asheville in the Bent Creek area. These were captured in 1982 aerial photography when their scars were still visible in the forested landscape. These air photos can be matched to lidar imagery to directly confirm what debris flow scars look like in the landscape. The GIFs below show this process, with yellow arrows indicating the upslope starting points (initiation zones) of the debris flows.

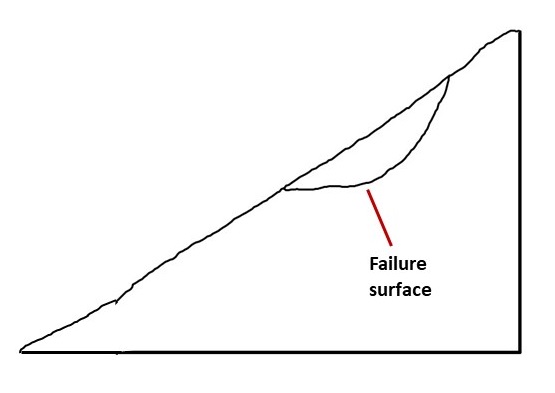

Debris flows like these begin as an initial landslide, producing a distinct scar in the landscape with steep, sharp edges where the slide began. This scar transitions into a visibly scoured track where the debris flow rakes saturated soil from the slope in its path, adding to the flow’s mass. The GIF below gives a general idea of this starting process and the scar that it makes, from the initial slide to the early phases of scour.

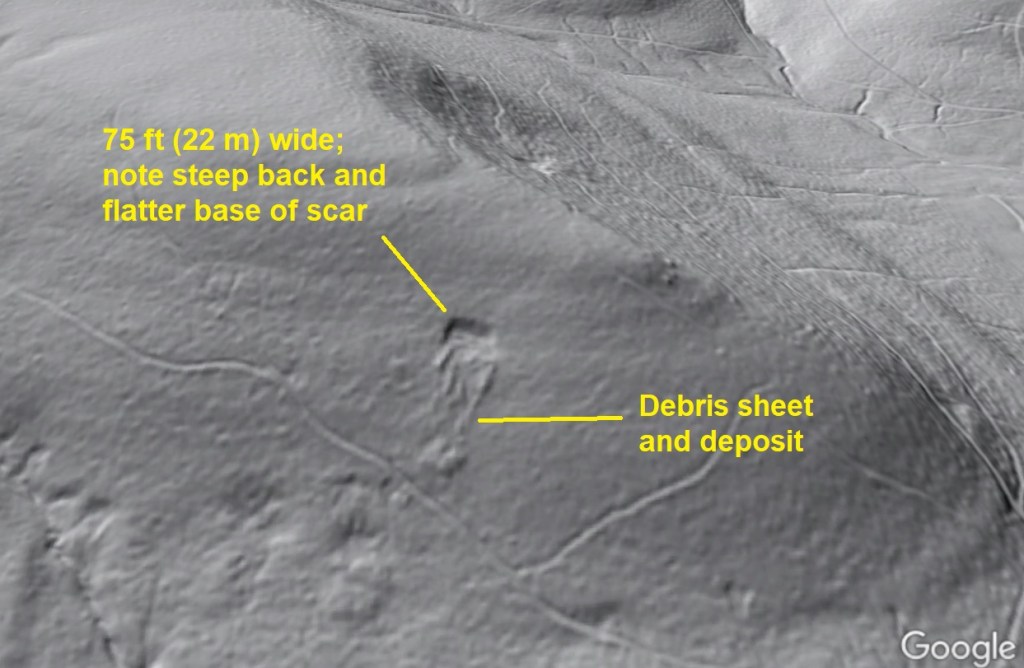

Within the grayscale world of lidar-derived hillshade imagery, debris flow scars can be distinguished from small, water-carved channels due to the effects of the initial sliding and subsequent scouring processes. Fluidized landslides similar to debris flows, but without the long, scoured track (referred to as “blowouts”), also produce distinct scars. The sketch below offers a basic summary of what you’re after as you peruse lidar imagery.

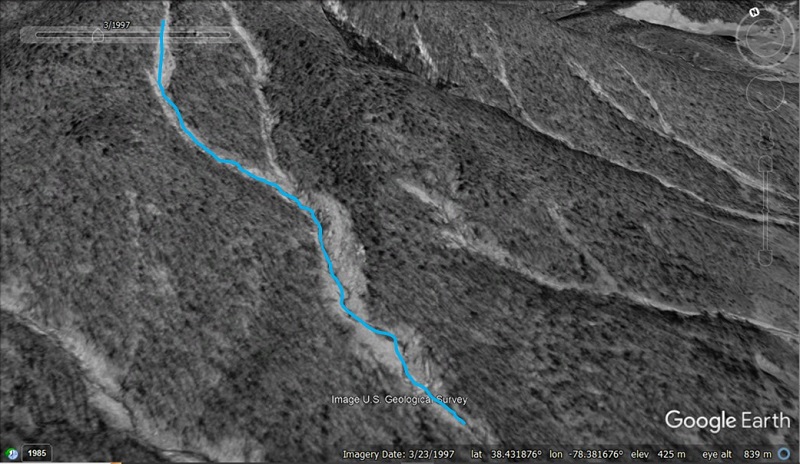

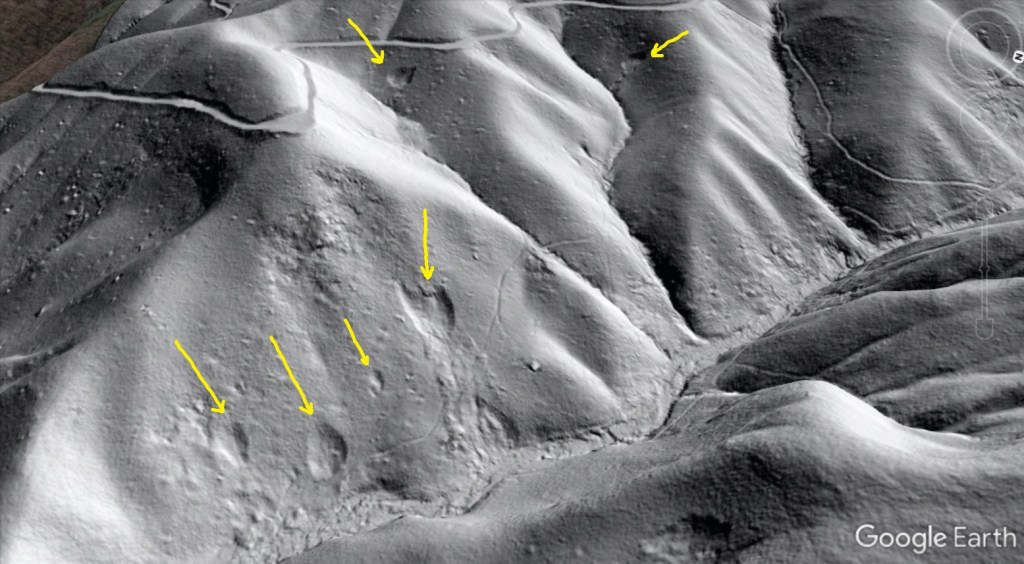

So, with this knowledge in mind, it’s time to take a look at Fires Creek Mountain. Clingman’s geography and distance estimates are always excellent, so I drew a line four miles due north from the Fort Hembree historical marker’s general area. The line met the top of Fires Creek Mountain at about 3.9 miles in a debris flow-susceptible area…not bad. The lidar imagery does the rest.

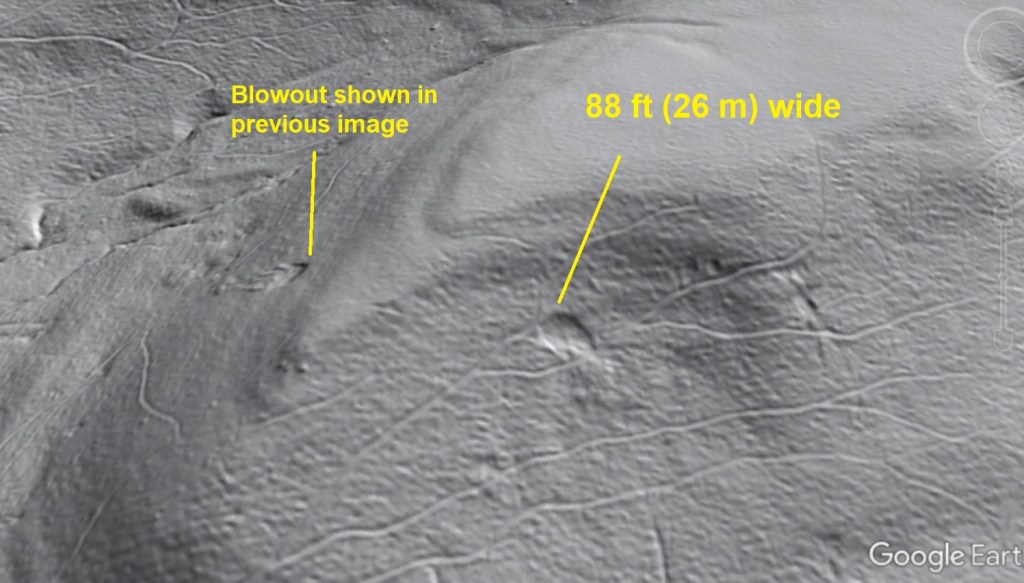

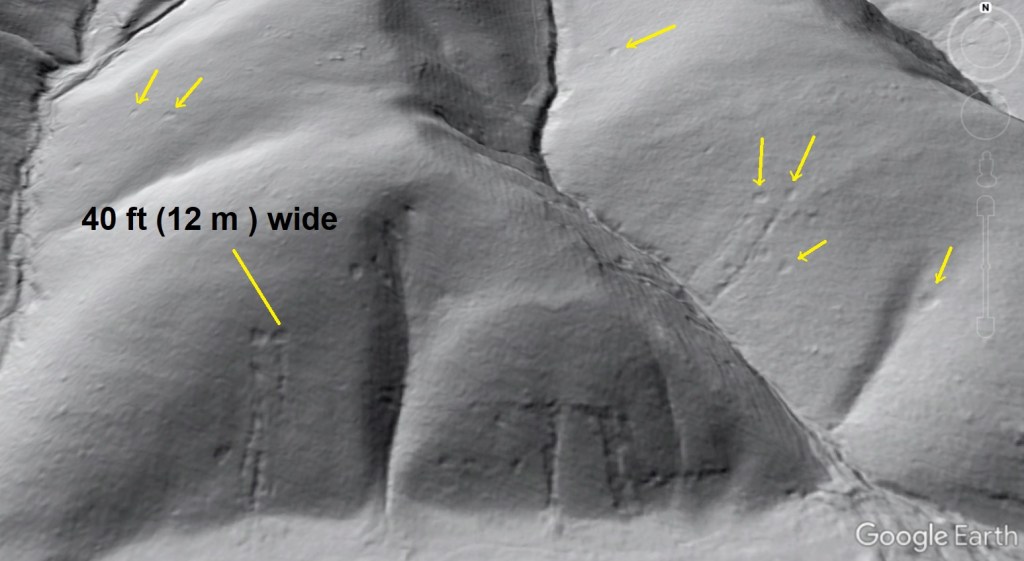

There are indeed an impressive number of debris flow scars on Fires Creek Mountain at the top end of the black line, exactly where they should be. Their appearance is unmistakable, and they distinctly cluster within a limited area as Clingman notes in his report. Yellow arrows point them out below; many more are visible in the zoomed-out view that follows. They aren’t labeled in the large view–see how many you can find.

The scars are well-preserved and look like the 1977 scars, though a bit worse for wear after 180 years.

This 1847 storm was likely an isolated storm “stuck” on the mountain ridges, given the limited size of the most intense debris flow activity. Clingman references observers in the valley below watching the storm on the mountain but not experiencing the intense precipitation themselves. Had this storm happened today (or in the era of easy photography, particularly aerial photography), it would have been intensely documented and firmly cemented in local lore. Today, it might make international headlines, particularly if someone caught a video of one of the debris flows reaching the valleys. How readily visible the debris flows and blowouts were from the valley below in 1847 is hard to know, but it was obviously eye-catching enough to have attracted attention and investigation from locals at the time. The images below show brown outlines over the visible features.

Extreme storms are likely to become more common in a warming atmosphere, but they’ve always been a part of the southern Appalachians. Helene’s impacts were exceedingly widespread, but more localized–and more intense–storms have happened in the past and will continue to happen in the future. It’s worthwhile to look back on these events and their impacts as a reminder that all sorts of things can happen in our region when conditions are right.

What happened to mountain slopes during Helene? Geologists are gathering information to prepare for the next storm

In the nine months since Helene’s arrival in western North Carolina, geologists have worked steadily to better understand how to reduce future landslide-related impacts on life and property. While landslide themselves cannot be prevented from happening under extreme precipitation conditions, decision making during, and particularly before, a storm can save lives and reduce damage to infrastructure and personal property. Understanding what made certain landslides more damaging than others requires both extensive fieldwork and study of remote sensing data, like lidar imagery. ALC Principal Geologist Jennifer Bauer and Project Geologist Philip Prince recently presented some of the findings of their post-Helene work in US Geological Survey seminars. Video recordings of the talks are linked below. If you have ever wondered what a geologist sees in one of Helene’s thousands of landslide scars, these videos will give a glance of how we do our work day-to-day.

Jennifer Bauer

Jennifer’s talk focuses on the use of landslide mapping and modeling to understand and (more importantly) communicate landslide hazard before storms hit. Understanding landslide potential in a given landscape requires that geologists understand the landslide history of a landscape. Landslide inventories involving both lidar imagery analysis and lots of boots-on-the-ground fieldwork help geologists learn what has happened in the past.

Once the geologic details that can produce landslides are understood (slope shape, slope steepness, soil type, etc.), models of potential landslide hazard zones can be developed. As Jennifer’s talk shows, the overwhelming majority of Helene’s landslides came from mapped hazard areas, but not every hazard area produced a landslide…this time. Hazard mapping can show mountain residents areas that are potentially dangerous is storms (don’t worry; it’s not everywhere-not even close) and help with decision making regarding where to live and how to prepare for the next big event.

Philip Prince

Philip’s talk is centered around the geologic details of Helene’s debris flow landslides. Debris flows are fast-moving, fluidized landslides that can travel long distances very quickly. Often called “mudslides,” debris flows actually carry huge amounts of rock and boulder debris and tremendous numbers of trees, so a debris flow impact is much more damaging than what might result from mud alone.

Philip illustrates where debris flows start in the landscape and how they accumulate so much material on their path downslope. A large debris flow could cover a football field with a few feet of mud, rocks and trees, but even small debris flows are surprisingly destructive. By understanding what type of geologic materials and slope settings produced debris flows during Helene, we can better understand what areas may be hazardous in the next event. Planners can also what parts of the landscape may be more susceptible to landslides when disturbed for building, as well as what areas at the foot of the mountains might be reached by debris flows.

Understanding debris flow landslides in the southern Appalachians

Before Helene’s remnants passed through western North Carolina, the boulder-strewn area in the photo above was covered with trees and buildings. A small stream flowed behind the wrecked buildings on the left of the photo. The damage seen here occurred suddenly on the morning of Friday, September 27, 2024, as a huge wave of boulders, trees, and mud surged down the small stream’s channel. This wasn’t a flash flood–it was a debris flow, a type of fast moving, fluidized landslide associated with heavy rainfall. The extent of the damage from the debris flow is visible in the before/after GIF below. The photo above was taken near the top of the GIF images, looking towards their bottom. The large building labeled above is visible near the bottom of the GIF images.

The small stream is visible trickling through the damage swath; water flooding alone from a stream this small could never approach the level of damage caused by the debris flow. Fortunately, no one was seriously injured in this particular debris flow, but many lives were lost in similar events elsewhere during Helene. Understanding these particularly dangerous landslides is a big part of storm safety in southern Appalachia. So, what are debris flows, where do they start, and what makes them so dangerous?

What are debris flows?

Debris flows are fast-moving, highly mobile, fluidized landslides transporting saturated soil, boulders, and trees downslope. They are specifically associated with saturated soil, which results from heavy rainfall in our region. Debris flows move like a liquid but contain large amounts of solid material–65% solids (rock, soil, and wood) is an average composition, with the rest of the flow volume being water mixed into the soil and rock. Often called “mudslides,” debris flows also carry large trees and boulders. Because of their solid content, debris flows are approximately twice as dense as water, so they hit with destructive force. They follow ravines and small stream channels downslope due to their fluid consistency, spreading over wider areas at the base of slopes until they lose their momentum. The sketch below gives a general idea of a debris flow’s start-to-finish journey downslope, from its beginning in a steep hollow to its damaging end on flatter ground at the base of the mountain.

Where and how do debris flows start?

Debris flows frequently start in steep hollows, or slightly concave slope areas, above the headwaters of small streams. They can also begin on road embankments, or any other landscape feature that can initiate a small landslide on steep ground. Debris flows are specifically associated with heavy precipitation and saturated ground. When a landslide starts in saturated soil, it liquefies and accelerates. When the liquefied landslide hits the saturated soil in its path, this soil liquefies as well and is added to the debris flow. Much like a snowball, debris flows accumulate more and more debris moving downslope, adding to their volume and destructive power. The GIF below shows the basic idea of debris flow initiation in an area like the one indicated by the red box in the sketch above. Note that the debris flow starts in rocky soil beneath a cliff, where rock fragments have accumulated to the point of instability. Due to saturation, once the slide starts, it liquefies, and then liquefies the soil in its path.

How do debris flows move?

Debris flows follow ravines and stream channels due to their liquefied condition, typically scouring large amounts of soil and stream sediment on their way down. Moving within the stream channel keeps the flow confined and intact. Collisions between soil and rock particles help keep the flow liquefied. A confined, thicker flow also loses less of the water trapped within it. Debris flows can move very quickly, often at speeds of 20 mph or more. They frequently run up onto the slope on the outsides of bends due to their speed. Their width greatly exceeds the width of the stream or creek whose channel they follow. The conceptual sketch below illustrates the scouring process as well as debris flow size relative to the “usual” stream in the channel, even during high water flow.

The scouring created by debris flows can be quite impressive; it greatly exceeds the potential for water erosion by small headwater streams. The picture below (taken upslope of the first photo in this post) gives an idea of what the effects of the scouring look like.

The leading edge of the debris flow contains trees and larger boulders picked up by the debris flow through its scouring action. Smaller cobbles and mud trail behind. Even small debris flows can transport surprisingly large boulders and trees due to the density of the fluidized soil (it “floats” boulders), making a debris flow strike on a structure incredibly destructive.

When debris flows exit tighter channels or ravines onto flatter ground, they often spread out, but remain mobile and destructive for some distance. In western North Carolina, many tight stream channels open onto flatter areas at the base of the steep slope. These flatter areas are older, accumulated debris flow deposits. The GIF below shows debris flows exiting a stream valley and spreading onto a flat deposit area, where buildings are destroyed. Though an unpleasant thought, this sequence of events played out many times during Helene (as well as during many other storms in our region’s history). The satellite photo below the GIF shows a bird’s eye view of the debris flow where the first photo in the post was taken.

Debris flow deposits are an indicator that an area can experience debris flows and should be developed cautiously, if at all. This often seems counterintuitive, as the flatter slopes suggest safety from landslides. In reality, these flat deposit areas are a main indicator of possible debris flow hazard. People already living in such areas should be aware of the hazard during heavy rainfall. In southern Appalachia, about 5 inches of rain over 24 hours produces conditions necessary to make debris flows possible.

This is the first post in a series of Helene-related posts discussing landslide events during the storm. Posts will be a combination of remote sensing interpretation and first-hand, on-the-ground experience. Our goal is to increase understanding of what happened during this event and help folks plan for future hazard.

Additional discussion of how debris flows fluidize can be found in this video. It’s an interesting process that isn’t fully understood, but the basics are outlined here in greater detail.

Is this the biggest boulder in the Appalachians?

by Philip S. Prince

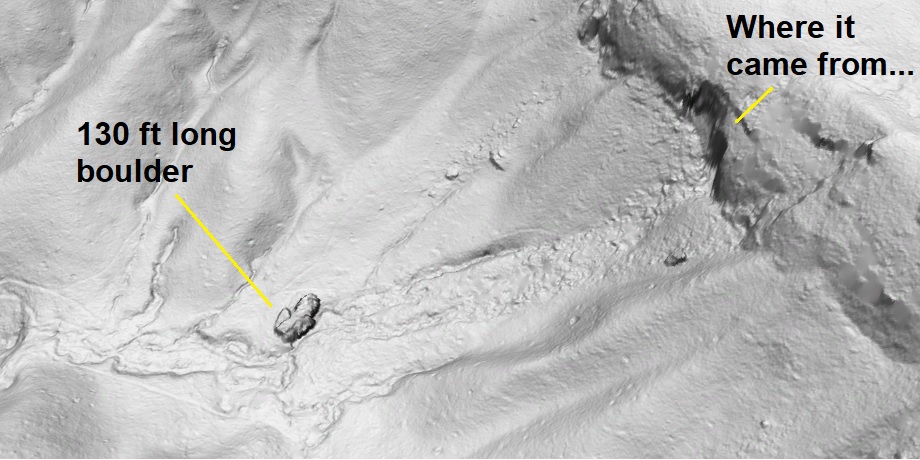

In Pisgah National Forest a bit northwest of John’s Rock, there’s a really big boulder in the woods. Like so many Appalachian geologic features, it looks really nice when viewed with lidar imagery. This boulder is particularly satisfying to look at because it sits alone on the floor of a small valley, and its point of origin on a cliff above is quite obvious. The boulder traveled about 800 feet to its resting place, and appears to have moved alone and not as part of a larger rockslide.

The boulder is about 130 feet long, 70 feet wide, and at least 20-30 feet thick, possibly more. It is composed of a granite-like rock, but it shows a different mineral alignment (a foliation) associated with metamorphosed rocks in the region. Despite its size, this boulder is not particularly dramatic when viewed from the ground. I tried to reproduce the ground-perspective lidar shot below during a field visit in December 2022. “A” and “B” label corresponding features of the boulder.

This boulder is actually so big that it’s hard to get a sense of its size from the ground. Enough soil has developed on parts of its surface to allow trees to grow, and the surrounding forest breaks up its outline. Adding a geologist stepping across a large crack in the boulder offers a bit of scale (lidar shot shows the crack’s location), but, ultimately, this thing is just too big to fully appreciate without a bird’s eye view.

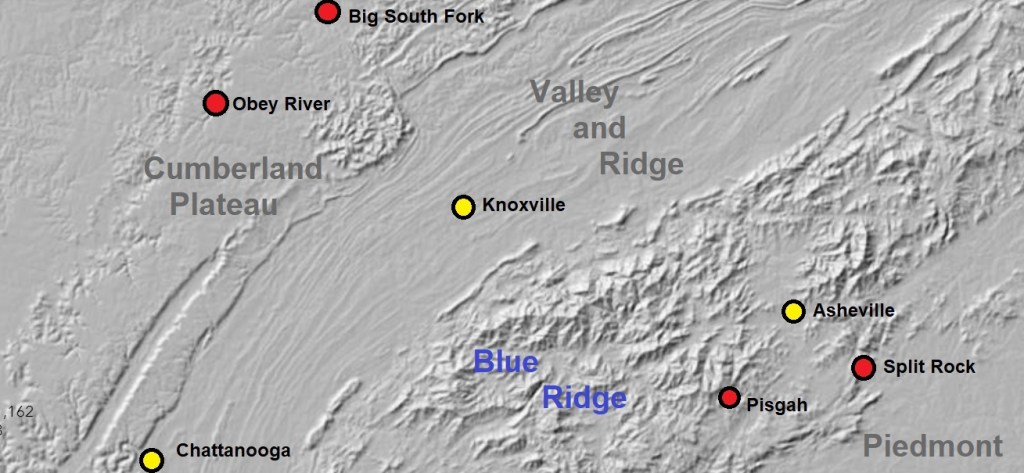

This boulder is definitely a monster, but is it really something special within the Appalachians as a whole? I thought this was an interesting question, so I prowled a bunch of lidar in boulder-prone areas to see what I could find. Big boulders need a tough, resistant rock mass as a source, weaker rock downslope to allow them to be undercut and detached, widely-spaced fractures to permit detachment of big blocks, and enough steepness to allow them to move away from the source outcrop. These combined parameters narrow down big boulder areas, making portions of the Appalachian topographic Blue Ridge and the sandstone-capped Appalachian Plateau the best places to look. I think the southern parts of the Appalachian Plateau are better, as aggressive freeze-thaw processes during the Pleistocene likely increased fracture density to the north and reduced maximum free boulder size. The few examples below are my top contenders for biggest boulder after cruising a whole lot of lidar. I did not, of course, look everywhere, but the search produced interesting trends summed up at the end of the post.

A definite contender for Appalachia’s biggest boulder is Split Rock on the Blue Ridge Escarpment in Rutherford County, North Carolina (it’s on private property and can’t be freely accessed). Split Rock is about 150 feet long in its longest dimension, though splitting into three pieces has allowed it to spread a bit. Its proportions are actually quite comparable to the Pisgah boulder and are probably just about identical if Split Rock were “un-split” and reassembled.

Like the Pisgah boulder, Split Rock is too big to really appreciate from the ground and could be easily confused for in-place bedrock outcrop. The photo below shows the edge of Split Rock at one of the namesake splits; the lidar shot shows the photo location.

Split Rock is composed of metamorphic gneiss-like bedrock that is distinct from the granite-like rock of the Pisgah Boulder. Split Rock’s most impressive detail is that it did not completely fall apart on its trip downslope, as the rock is full of weaker mica-rich horizons along which it might break apart. Its variable compositional layering (which is a metamorphic foliation) gives it the ragged edges visible in the field photo above.

Several boulders in the 100 foot size range occur within Split Rock’s part of the Blue Ridge Escarpment, but the most prolific giant boulder province in southern Appalachia–and likely all of Appalachia–is the western edge of the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee and Kentucky. Here, thick sandstone layers undamaged by thrust faulting and folding are well-suited to forming giant boulders. Folded and faulted layers in the Valley and Ridge contain too many fractures to make bigger boulders than the Plateau sandstones, and mica content and general weatherability in the Blue Ridge limit huge boulder potential outside of isolated extreme examples.

The slope above the Obey River shown below is a good example. The boulders looks small, but they are actually just shy of the size of the Pisgah boulder. Boulders this size are actually very common in this area, where soluble limestone beneath the sandstone caprock and a history of river incision set the stage for moving huge blocks downslope. The boulders shown below traveled as part of a larger landslide, but give the appearance of having moved independent of one another after the initial failure of the cliff line.

To the northeast, on the Big South Fork River near the Kentucky border, two large sandstone boulders detached from a cliff outcrop and plowed a clearly visible path downslope toward the river. the largest boulder, closest to the river, is about 115 feet long in its longest dimension.

A friend provide me with a photo of the 115 ft boulder, taken right at the end of the yellow leader line in the image above. Notably, these big sandstone boulders are not deeply buried in soil like the Pisgah boulder and Split Rock.

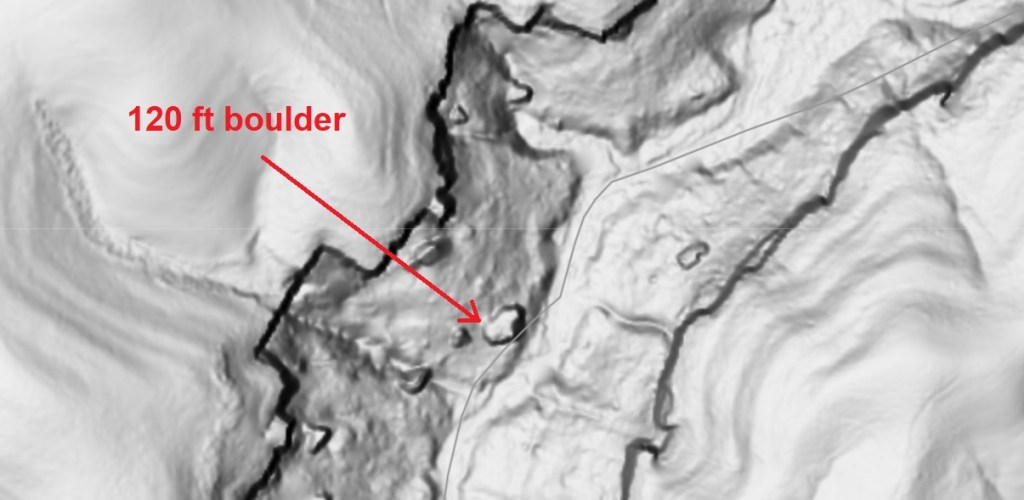

Further north in Kentucky, the Red River Gorge area is also full of ~120 foot sandstone boulders. The lidar shot below (taken from the Kentucky Geological Survey’s site) shows two 120-footers, indicated by red arrows. Boulders between 50 and 100 feet along their longest dimension are extremely common in this area. The joint-controlled, right-angle patterns in the cliff lines in this area are also interesting to check out.

The zoomed-in shot below shows the lower right boulder, which has traveled about 400 feet from the cliffline.

If you’ve paid attention to the measurements, 120 feet or so seems to be a common measurement for the biggest boulders to be seen in boulder-prone Appalachian landscapes. The Pisgah boulder and Split Rock aren’t alone in the southern Blue Ridge area; there are more 100-120 ft boulders to be found there, but they aren’t as numerous as boulders of that size in the Appalachian Plateau. In both areas, though, maximum size is intriguingly consistent, though only among boulders that have moved several boulder lengths from their source outcrops. Bigger chunks of rock can be found right along cliff lines, but these detached blocks have not actually moved or slid and experienced the associated physical forces. I imagine that the ~120 ft number is some reflection of the physical properties of the boulder-forming rock unit, both in terms of how it resists falling apart during sliding and how it controls topography to make cliffs and slopes to source and move big boulders. The image below compares sizes of the some of the boulders, with zoom adjusted so that it’s possible to directly compare them.

So, is the Pisgah boulder unique in any way? I think so. It is definitely at the top end of boulder size within Appalachia, though you can’t justifiably conclude it’s bigger than a reassembled Split Rock or something lurking in the Cumberland Plateau. It also traveled a significant distance from its source outcrop. This is notable because it contains aligned mica-rich layers that present plains of weakness along which it could break apart. The fact that the Pisgah boulder (and Split Rock) traveled hundreds of feet at their significant sizes and ended up in (mostly) one piece is impressive and probably the result of some amount of coincidence. Thick-bedded, very quartz-rich sandstone boulders lack aligned mica layers, so the potential to move a single huge piece of rock without breakup might be greater.

I don’t know how mechanical properties of the respective rock types would compare. Tensile strength of all Earth rocks is quite low compared to compressive strength, so rock doesn’t do well when forces try to pull it apart. Mica-rich zones or zones of extreme mineral weathering might lower tensile strength even more, so non-sandstone rocks might be less likely to hold together in single chunks than a physically hard and chemically tough quartz-rich sandstone. I also don’t know how these boulders move. I have always assumed that they slide, as tumbling would subject them to forces that would break them down to smaller pieces (that whole tensile strength thing, again). Check out what happens to the big block of rock in Switzerland shown below at this link.

Ultimately, geology superlatives (biggest, oldest, etc.) aren’t really worth much, but trends and patterns are useful in understanding how landscapes work. I looked at hundreds of big boulders, and not too much over 100 feet in the longest dimension is as big as you’ll see for a boulder that has moved significantly. This size is well-represented in certain sandstone-rich areas. Notably, sandstone-capped areas in Kentucky and Tennessee have, on average, bigger boulders than sandstone-capped portions of West Virginia. This may reflect local geologic details, climate and latitude, or both. The Blue Ridge serves up arguably the biggest boulders, though by an insignificant margin, and they are much less numerous due (presumably) to rock type details. Perhaps most interesting is that no one has ever seen a boulder the size of these biggies actually moving in the Appalachians, and none of them appear to be freshly emplaced. What makes them move and whether or not they do much moving under modern-day climate conditions is a big question in and of itself.

Using LiDAR and a 121-year-old drawing to locate a 1901 debris flow in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains

Philip S. Prince

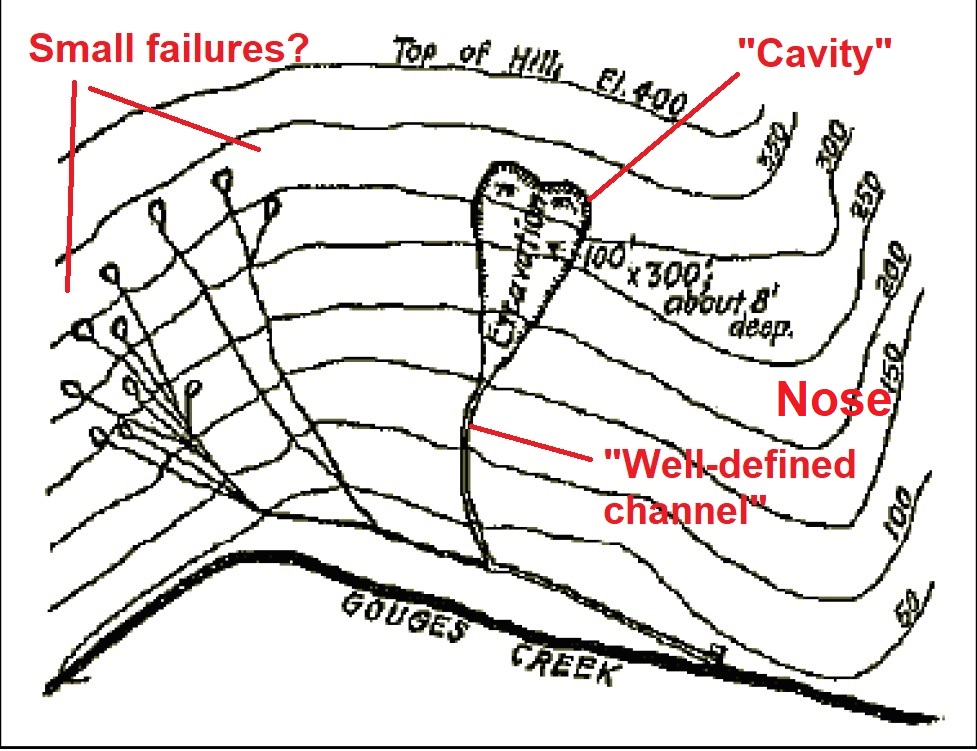

In 1902, E.W. Myers published an account of a 1901 flood (the “May Fresh”) and its effects on the mountain landscapes of western North Carolina. Included in the report is the following sketch of a debris flow, sourced in digital form from Anne Witt’s ResearchGate page. Notably, no indication of cardinal directions or distance to nearby landmarks are included in the sketch, making the exact location of the debris flow (whose indicated size is impressive!) uncertain.

Also excerpted in Anne’s work is Myers’ text description of the feature he drew.

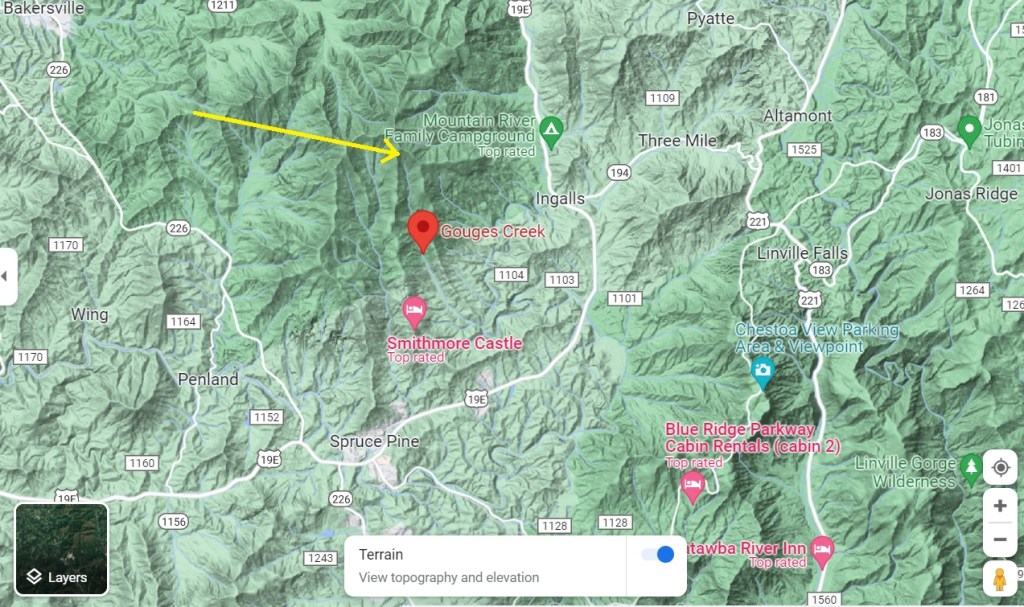

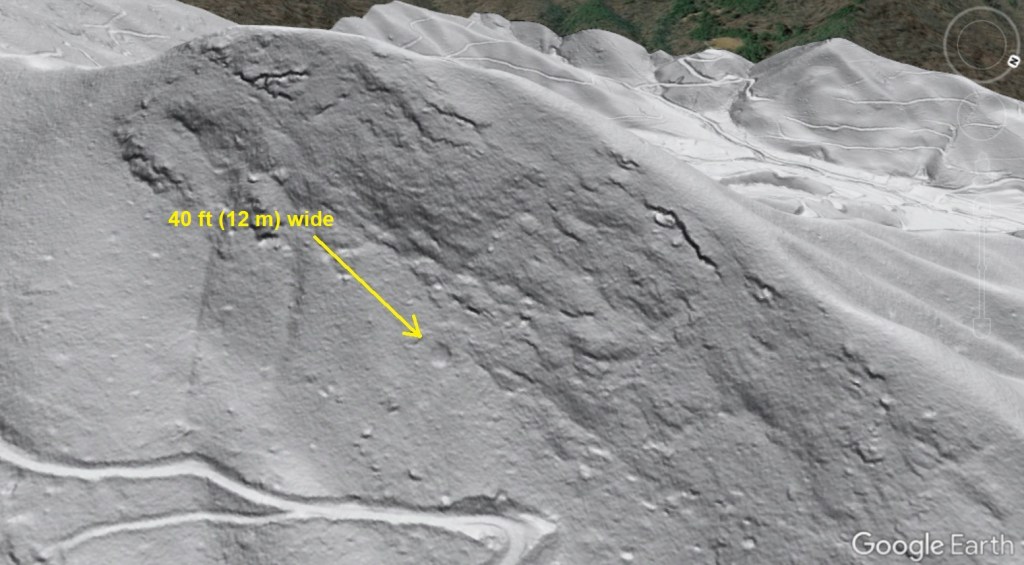

I thought it would be interesting to try to find this debris flow based on the information Myers provides. With the sketch and text, Myers indicates that the debris flow entered Gouges Creek from a downstream-left direction, left a “heart-shaped” scar on the hillside, and was near a ridgeline and summit and generally very high within the surrounding landscape. In the era of high-resolution LiDAR imagery, these details turned out to be sufficient to locate the debris flow on the Mitchell County-Avery County line north of Spruce Pine, North Carolina. A LiDAR hillshade image of the slide, as well as a Google Maps image of its location, are shown below. The slide is not large in the context of the entire mountainside, but the heart-shaped scar from the initial failure (end of yellow arrow), downslope scouring, and proximity to the ridgecrest/summit are clearly visible.

Locating the debris flow was easier than expected. It is the only significant debris flow on Gouges Creek (not to be confused with Gouge Creek and many other Gouge place names in Mitchell County), and its distinct heart-shaped initiation zone distinguishes it from other debris flow features on nearby slopes. A close look at the “heart shaped” scar as revealed by LiDAR hillshade makes clear what Myers hoped to capture with his sketch.

A 2023 geologist of the Google Earth and drone era has to remember that Myers drew his 1901 or 1902 map sketch by interpreting from the ground, and he was quite successful in capturing the general layout of the landscape around the debris flow. No indication of his vantage point for making his sketch is given in the drawing of the text excerpt; he may have been along Gouges Creek or viewing from the ridge to the south. The images below compare the actual topography to Myers’ sketch, with labels on notable features. The light blue lines in the LiDAR image indicate faint channels with may generally locate the many small failure Myers illustrated. No significant trace of these failures is visible in today’s landscape.

Myers did overestimate the size of the failed area, but he didn’t do badly assuming he was visually estimating from a distance. The actual scar is a bit smaller than he suggested, but is still quite significant. The LiDAR detail below shows the real dimensions of the scar, assuming Myers length estimate was made from the top of the “heart” to where the failed area narrows to the scoured channel.

Myers also reported that the material which moved during the debris flow seemed to have “disappeared utterly,” indicating that the flow was quite mobile and did not deposit significant material in Gouges Creek near the failure itself. This observation is reflected in LiDAR imagery, where no significant deposit is visible in the area shown; instead, scouring continues down the Gouges Creek channel. The yellow arrow indicates the heart-shaped initiation zone.

Myers did not use the term “debris flow” (I don’t think it existed at the time!), but his description captured some principal components of debris flows, included the “excavated” initiation zone (“evacuated” would be used today), erosion or scouring of a track into the soil profile below the initiation zone, and the high mobility of the moving material. The simple physical model below shows this scouring process, during which the once-solid material that detached to produce the debris flow fluidizes and erodes the slope as it travels downhill. Compare the pre-flow “normal” channel texture to the post-flow scour. This erosion adds material to the flow, making it grow in volume. A key distinction between the model and a real debris flow is that the model uses dry, low friction materials; a real debris is a very “wet” feature that occurs due to soil saturation as a result of extreme rainfall.

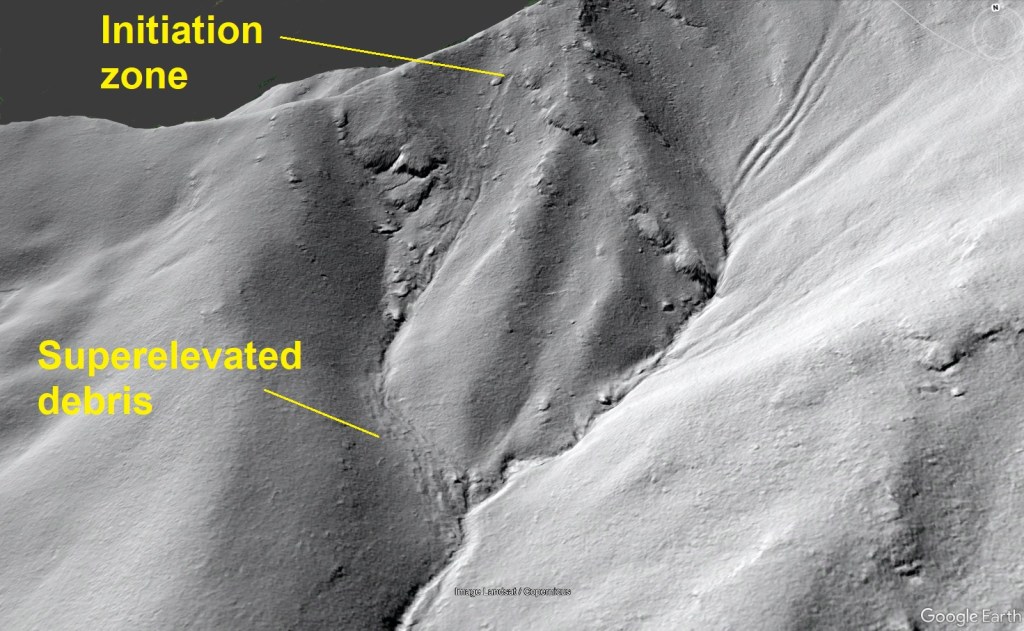

LiDAR reveals other past debris flows in the area, including an impressive feature (left arrow, below) northwest of the Gouges Creek flow. The GIF shows the outline of the flow and its path from the initiation zone downslope.

This debris flow has a less impressive scar/initiation zone, but the flow did leave traces of a process known as “superelevation,” which describes a flow sloshing up the sides of bends in the channel carrying it due to its momentum.

The GIF below shows another physical model, which demonstrates superelevation. Note how the flow runs up the channel banks where bends are present.

I haven’t read the full Myers report, so I don’t know if the superelevating debris flow is discussed or if it is even from the 1901 “May Fresh”–there are plenty of other extreme precipitation events to choose from. In any case, the physical characteristics of the superelevating flow are sufficiently distinct from the Gouges Creek debris flow to distinguish them with LiDAR imagery with the help of Myers’ sketch and description.

The scar and track of the Gouges Creek debris flow are now located in an entirely forested landscape, and would be visible only from the ground due to tree cover. With LiDAR imagery, however, the feature is impressively visible and fresh-looking despite being 116 years old at the time of LiDAR data collection.

The Gouges Creek debris flow did destroy a log cabin; apparently it was unoccupied or uninhabited, and no one was hurt or killed. While modern land use patterns are different in the North Carolina Mountains, debris flows still represent a significant threat to life and property due to their extreme mobility and fast speed (you can’t outrun one). Were a debris on the scale of the Gouges Creek event to occur in a more populated part of the mountains today, the potential for very negative outcomes is quite high. Mountain residents need to be aware of the weather conditions that produce debris flows, as well as their potential paths, to stay out of harm’s way. Records of past events like Myers’ report are useful reminders of the potential for extreme rainfall and debris flows throughout the North Carolina Mountains, though events may be separated by years or decades in a given area.

Did humans cause this Alleghany County, Virginia, mountaintop to drop several feet?

by Philip S. Prince

*Note: There is indeed a sand model in this post, but it’s near the end…

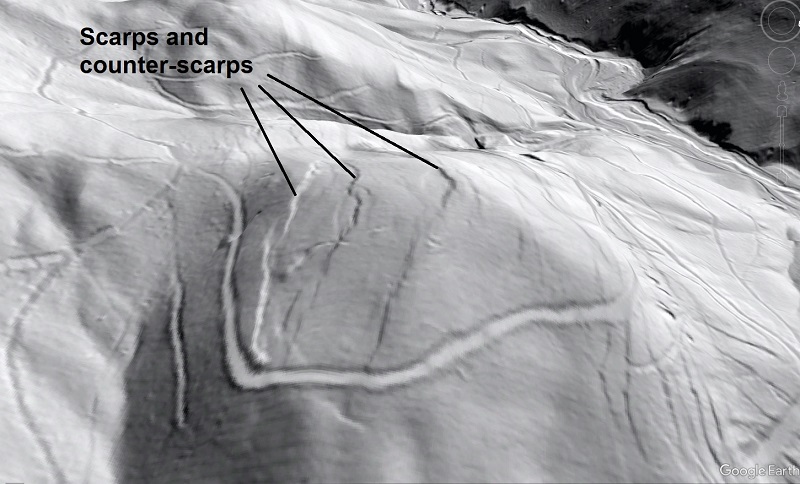

Well, it’s more of a hilltop, but it has dropped several feet since iron mining was active on its lower slopes in the early 20th century! The summit of this unnamed hill southwest of Low Moor, Virginia, hosts conspicuous scarps that define a graben, or downthrown block, that has sunk about 6 ft (just under 2 m) relative to the surrounding hilltop. The graben is a bit over 300 ft (100 m) wide. The scarps are subtle but very clearly visible in 1-meter resolution, lidar-derived hillshade imagery. Results of iron mining are visible at lower right in the upper image below (more on this later, for sure).

The scarps (which face outwards and downhill) and counter-scarps (which face inward, or towards the upslope direction) do not appear to cut road grades on the slope. They do, however, offset a prospect trench within the subsided graben. The slope movement thus post-dates the trench, but was likely gradual and episodic over the course of months or years. I don’t know if movement would have been discernible during the period that mining was active, or if it completely post-dates work at the site.

Disturbance of the prospect trench puts movement on the scarps within, or after, the iron mining period, which is consistent with other iron-mine related features in Alleghany and Botetourt Counties in Virginia. I have written about these other iron mine-related landslides before (click here), but the summit graben shown here is unique because of its position on the slope and its 300 ft / 100 m width relative to the overall scale of the affected hill. Because of the graben’s position on the hill and its width, deformation is likely seated very deep within the hill. The slow-moving GIF below shows an interpretive cutaway of the slope, with shear planes sketched in from the shape of the slope and reasonable angular relationships.

Interpretive is the key word here…I have not even been to this site in person, so I am just inferring a possible subsurface structure from surface deformation and the size and shape of the hill and graben. That said, the graben is quite large with respect to the size of the hill, and its position so far from the toe of the slope definitely implies very deep-seated movement. This is certainly not a thin, translational bedrock-involved slide of the type that is common within the Appalachian Valley and Ridge. The outwardly-moving hillslope is not a dip slope in the first place, and the scale and position of the graben make a shallow translational explanation impossible. A slightly zoomed version of the subsurface interpretation is shown below. Note that the cut of the diagram is a bit out of plane of the oblique image and slightly exaggerates relief and the thickness of the moving area.

Where does the iron mining factor into the story? Highwall surface mining for limonite ores occurred along the foot of the hill in the early 20th century. The workings were not exceptionally large, but they did tend to make contour-parallel cuts along the foot of the slope. The largest of these (the one visible at lower right in the post’s first image) appears to have experienced a major collapse. The other cuts also show indication of slope movement, though it is less pronounced. Mined areas and their location with respect to the graben are shown below.

Even though the mined areas aren’t exceptionally extensive, they obviously destabilized the slope in proximity to the cuts; small parallel scarps are visible upslope of the mined areas in the image above. Presumably, this destabilization and associated slope movement turned out to be very far-reaching, allowing the whole hill to expand a bit laterally and force graben subsidence. The following GIF offers a simplified, cartoon-style interpretation of the process.

This style of slope movement suggests that hillslopes in the area may be near a deep-seated stability threshold that makes them susceptible to modest but volumetrically significant movement in response to very minor surface modification. This susceptibility may be a reflection of bedrock geology and structure. This area is underlain by a complexly folded and faulted sandstone and limestone interval with thick shales above and below. The result is shale-cored mountain topography that is “propped up” by the strength of armoring sandstones. Additionally, the area has experienced considerable geologically-recent relief production due to its location in the James River basin, so slopes have grown taller and steeper as valleys have lowered. Given these background conditions, potential slope behavior under disturbance could be expected to be different from the behavior of a more geologically consistent, lower relief landscape.

I think the most interesting aspect of this human-induced topographic “adjustment” is how a very modest excavation produced an equally modest slope movement, at least in terms of overall displacement of the moving mass of hillslope. None of the mining-related slope movements in the area appear to have produced rapid, long-runout slides or flows; all resulted in slight shifts that are really only discernible with lidar-derived imagery. All are reforested, and lidar imagery does not suggest any are subject to imminent significant movement. I tried to set up a simple physical model to capture this behavior. Two trials are shown below. The model hillslope is constructed of a cohesive sand-and-flour “shell” over a weak glass microbead core. With disturbance of the toe of the slope, a small, lurching failure occurs, reestablishing equilibrium and stability with a tiny but obvious movement.

Setting these models up to produce this style of failure was a worthy challenge. Their behavior is definitely material-specific; cohesive or loose sand alone (or microbeads) won’t do it. The slope has to be just unstable enough–and mechanically appropriate–to settle slightly with minor disturbance to the toe of the slope. The failures are not as deep-seated with respect to the slope as the real graben scenario, but they are deep enough to produce back rotation of the head of the slide with very little displacement, as shown below. Scarps and counterscarps are marked with hachured lines.

While these models experience rapid, one-time movement, the amount of movement necessary to reestablish stability is very small. This was the goal of the models, specifically as a way of connecting the slope’s mechanical architecture to failure behavior. A very brief YouTube video linked below shows the actual failures at full speed. It seems ridiculous to go to great lengths for such tiny movement, but it was much more challenging than producing a high-runout model, for sure.

While the summit graben feature is an extreme example, mine-related failures abound in this area. The image below shows other failures just up the valley from the graben feature. Again, cuts on contour appear to be the issue, but slopes responded with modest movement. In the image below, a large area of slight displacement is clearly visible above a highwall cut. The hill with the graben is just outside the field of view to the right. More examples exist just southwest of this one.

The location of these slope has largely spared them from modern-day engineering, but it is interesting to consider how they might respond to more carefully planned modification! It also invites comparison to the well-documented Rattlesnake Ridge landslide in Washington.

Scale model landslides show what happens if you mess with a landslide toe

by Philip S. Prince

The two images below show the same model landslide at different points during its evolution. The lower image, of course, looks much uglier, with a broken-up slide block and huge, looming headscarp. Notably, the thick toe labeled in the upper image is conspicuously missing…(spoiler: you can watch this model evolve at 1:04 in the video link at the end).

So, how did the slide progress from a not-too-impressive feature to a mangled mess? The answer relates to that toe, or rather its absence in the lower image, with a few details of the slide’s shape thrown in (more on that in a bit). Toe removal, however, is the main idea, and removing a landslide’s toe invites trouble in the form of probable continued movement. A slide like the one shown above (that is, not a rapid, flow-type slide) can move until the toe becomes large enough to resist the driving load that led to slide movement, assuming that friction on the sliding surface remains low. Removing the toe allows driving load to overwhelm resistance again if friction on the slide plane is sufficiently low, leading to renewed movement of the slide. The GIF below illustrates this idea in basic terms. I-26 drivers in western North Carolina might appreciate the pink excavator…

A well-developed landslide toe can therefore be regarded as the “prop” that supports the rest of the upslope slide mass atop the weak failure surface. Altering a toe is often a fast track to instability and slide reactivation. The simple model shown in the GIF below demonstrates toe development, removal, and reactivation in a slide that behaves much like the one drawn above. When toe material is removed, the slide advances until enough supporting toe is restored. Note that this model is much “neater” than the model in the first images!

Continued toe removal leads to continued motion, particularly in the model above, as the slide mass does not break apart and continues to exert a strong driving load on its base. Once the slide mass is broken along its edges (lateral scarps), it no longer has the small amount of support provided by the cohesion (“stickiness”) of the model material. Real rock and many soils have some cohesive strength as well. It is never very much, but it does provide a component of resistance to sliding. Once the material is broken, however, this tiny bit of resistance is lost, and ongoing movement of the slide due to toe removal is that much easier. In a model like the one above, the entire slide block can be consumed by removing the initial toe and continuing to remove material pushed out into the new toe.

Weakness and potential instability associated with a landslide can persist for a long time after the slide becomes dormant and is not obvious in the landscape. Nearly “invisible” old slides that aren’t currently moving can be reactivated long after they stopped moving by disturbing the slide toe. Using lidar to identify such old slides is a key part of pre-construction site assessment.

Destabilization of landslides by toe removal is a very real thing, with actual scenarios–both large and small–arising from construction and natural stream or wave erosion. Many are slow and manageable, but they can be ongoing, hard to stop, and quite expensive over time. A famous example I am fond of is shown below. This is the “Galloping Highway” slide in Giles County, Virginia, along US 460. The toe of an older, dormant slide was removed for the highway cut, initiating literally decades of reactivated–and slowly ongoing–movement. This slide is, in effect, a real-world example of the previous GIF where an “invisible” slide came back to life. The slide block is nearly 1,000 feet across along US 460.

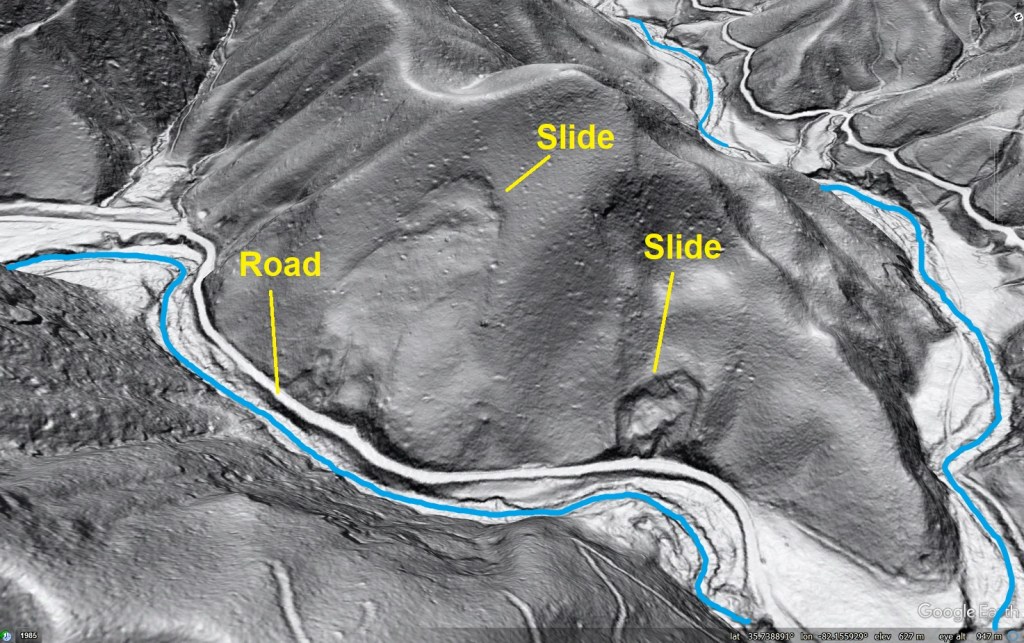

The slides shown below are in McDowell County, North Carolina. Both are situated for possible reactivation due to the road cut that has impacted their toes as well as steady stream erosion of the toes, which would pre-date the road cut. I imagine both have a reactivation history due to stream erosion; the smaller slide on the right appears to have reactivated more recently due to the road cut.

The next impressive example is along a railroad grade in western North Carolina. Lumpy areas just above the tracks look very much like recent reactivation, and a faint toe seems to be pushing out of the base of the cut. Two logging roads at the right of the slide are offset by scarps, indicating recent slide movement. The relative impact of the railroad cut and possible removal of material from the slide toe as it slowly pushes outward can’t be discerned from lidar, but the offset roads and ugly toe indicate this one definitely deserves engineering attention.

The slide above looks quite different from the first few examples and provides a nice way to circle back to the very first model in this post. The shape of a landslide’s failure (sliding) surface strongly impact what happens to the sliding mass as it moves downhill. A slide on a failure plane with constant slope can move intact, but a failure plane with changing slope requires the slide mass to constantly change its shape as it moves. If the failure plane becomes less steep, the top of the slide has to stretch to match its shape, forcing cracks or new internal scarps to form. The uppermost part of the slide can actually tilt backward until a depression forms (see above and below). The more the slide moves, the more exaggerated the cracking, internal breakup, and back-rotation of the upper part of the slide become. The GIF below illustrates the initial phases of the concept.

Obviously the gap below the slide block can’t exist…the collapse and stretching of the block are constantly developing as it moves. Physical models offer a nice way to show this process in action. Note how the cracking accompanies the backwards tilting of the upper part of the slide. This model is the last one shown in the video link.

So what happens to these early cracks if the toe is removed and movement continues? With the right failure surface shape, something like the very first model develops. This is where the video comes in. Linked below are more reactivated landslide models, including all those shown above. Some really fall apart with toe removal and continued movement; in others, a smaller and smaller block continues downslope with little or no internal break-up. I assure you that this is the ONLY place you will see this many model landslides in one place, whatever that may mean! The two styles of slide described in this post are represented. They can be distinguished by how much the slides break apart as they continue to move after toe removal. I think it’s cool to watch their motion all at once. It beats trying to piece together months or years of episodic movement!

Impressive (and frightening!) debris flow superelevations in the Virginia Blue Ridge

by Philip S. Prince

Debris flows move fast, making them an exceedingly dangerous type of landslide. “Fast” is always a relative term, but in the case of debris flows, speeds of 30 or 40 miles per hour (~50-60 kilometers per hour) are quite reasonable. Debris flow speed is often sufficient to cause the flow to “run up” the slope on the outside of bends in the channel the flow is following. The result is a scoured track notably higher on the outside of the bend than on the inside. This is “superelevation”–the “sloshing” of a flow up a slope due to its speed and momentum when it encounters a channel bend. The sketch below illustrates the idea.

The sketch actually contains a number of superelevated areas due to the bends in the channel. Each is characterized by asymmetry of the damaged, scoured area–higher on the outside of the bend than the inside. The GIF below puts the process in motion. The key point to look for is the flow running up the slopes as it rounds the bends in the channel.

The GIF exaggerates the process for illustrative purposes, but real-world examples of the superelevation concept can be quite dramatic. The image below shows the results of a Jun 27, 1995, debris flow in Madison County, Virginia, near Graves Mill. The scoured area clearly “swerves” away from the blue stream channel due to significant superelevations around bends. Notably, scour from the flow reached 290 feet from the stream channel in the foreground, where moderate slope offered less resistance to superelevation. At the end of the yellow arrow, the flow superelevated about 52 ft (16 m) up a steeper slope.

The ~52 ft superelevation site was photographed soon after the event. A particularly impressive photo is shown below, and the source report (Eaton et al., 2004) can be found at this link. The small red dot in the image above shows the approximate location from which the photo was taken. Note that the flow scoured trees and soil away, leaving bare bedrock. Obviously, structures in the path of a flow like this would not stand a chance.

As indicated by the caption of the photo, superelevation height is used to estimate debris flow velocity, with the 52 ft run-up suggesting a ~45 mph speed. At this highest superelevation point, the flow had traveled about 3,100 ft (940 m) and descended 885 ft (270 m) in elevation. The image below shows the 52 ft superelevation point (yellow arrow) in relation to the initiation zone of the debris flow. Note the number of flows in the area, a result of the extreme but localized precipitation associated with an atypical thunderstorm (check out this link).

As shown in the earlier GIF, this flow produced a number of superelevations due to slight bends in the stream valley the flow followed. Bracketed yellow lines show them in the image below, with the 52 ft feature near the center of the image.

To the east of this flow, a smaller flow produced another impressive superelevation. The following images show the flow’s track with and without a bracketed yellow line to indicate the superelevated zone. I am not sure exactly how high the flow reached here, but Google Earth suggests the height approached 48 ft (15 m).

A notable aspect of the imagery shown thus far is that it was taken soon after the actual debris flow events, likely in 1995 or 1996, as no vegetation has returned to the scoured flow tracks. The area looks much different today, but 1-meter resolution lidar imagery preserves evidence of the superelevations. Seeing the scoured areas may take a bit of focus, but they are definitely there, and can be nicely matched to the 1995 (?) imagery. The GIF below transitions between the 1995 imagery, current imagery, and a lidar hillshade/slopeshade image.

Traces of the superelevation to the east are visible in lidar imagery as well. The GIF below cycles through the same imagery types. This example is equally subtle but readily identifiable once you know it’s there.

In areas affected by debris flows sufficiently long ago that forest recovery largely obscures scoured flow tracks, lidar imagery can provide useful information about flow paths and superelevation potential. All of mountainous Appalachia can experience destructive and potentially lethal debris flow events, but the details of flow behavior can vary between sub-regions with different rock and soil types and different slope geometries. Studying past flow behavior can help geologists increase understanding about potential slope behavior during extreme rainfall events. This information can, in turn, inform planning and land use decisions, particularly when human safety is a consideration.

The 1995 Madison County debris flows are also an excellent illustration of how localized extreme rainfall and debris flow occurrence can be. The image below shows a larger view of the setting of the two superelevated flows described above, which are indicated by yellow arrows. Notably, debris flows are restricted to the southeast slopes of the mountain, where the superelevated flows occurred. Just across the ridge, no flows or landslides of any kind occurred.

The extreme rainfall (~30 in or 76 cm in 8 hours or less) that produced the debris flows resulted from upslope flow of moist air into a small but very intense thunderstorm. The details of the process are described in the second paper linked above (and again here), but a takeaway is that wind direction, altitude of winds, and the shape of topography “funneled” moist air upslope and into the storm to focus the catastrophic rainfall on a small area. The interplay of topography, weather, and slope geometry in this Madison County, Virginia, example nicely illustrates how meteorologists and geologists can support each other’s work to help people avoid debris flow hazards.

Blowout landslides, part 2: Material movement, and did anything actually “blow out?”

by Philip S. Prince

“Blowout” is definitely an unusual name for a type of landslide, and even the guy who came up with the name (William Eisenlohr, Jr., in 1952; link here) didn’t seem to like it. The purpose of the name was to capture the apparent type of movement associated with these slides, which eyewitnesses described as water and soil “bursting forth” from the ground during a 1942 storm which delivered over 20 inches (>500 cm) of rain within just a few hours. The lidar image below shows one such slide, and the scar (“hole”) and trails of debris leading downslope seem to fit nicely with this suggested style of movement.

So, did water actually gush up out of the ground and blow this material out, as the “blowout” name implies? In the case of the feature above, definitely not. Water would certainly have played a role in this slide’s failure, but only in the tiny spaces between soil and rock particles. There, it reduced interparticle friction and significantly weakened the soil–there was not a “broken water main” inside the slope. The slide shown above would, however, have appeared to burst or erupt out of the hillside, and probably quite quickly, with the sliding material rapidly turning into a fluid and cascading down the slope due to its extreme saturation. A look at some of the details of the slide scar’s shape explains this style of movement.

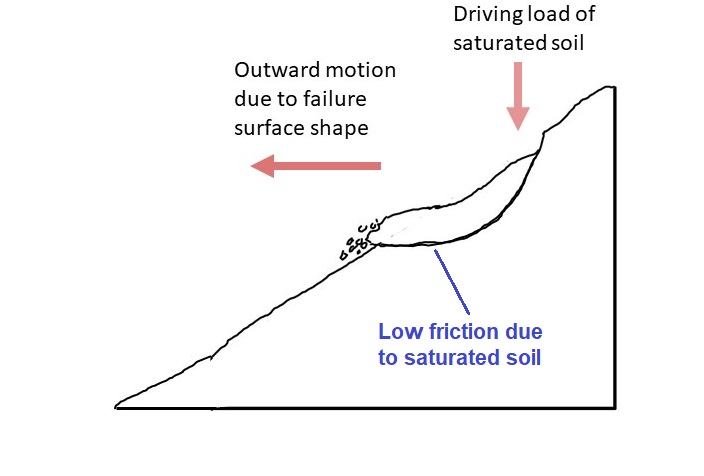

A specific detail of all of the blowout-style features highlighted in the previous post (link here) is the shape of their failure surface–it is curved, being much steeper on its upslope side and much flatter on the downslope side. The simple cross section sketch shown below illustrates this shape.

The intact, non-sliding hillside is much steeper than the downslope portion of the failure surface, so material moving along the failure surface would actually move outward from the failed area before gravity took over, requiring the slide material to collapse back down to the slope. Many of the blowouts have tall, steep headscarps (upper portion of failure surface), which would provide considerable driving load to push material out of the failed area. Once clear of the failure surface, the sliding material presumably quickly broke apart and fluidized, giving the impression of wet material “blowing out” from the hillside flowing over the slope.

Soil saturation due to the extreme rainfall, along with pore water overpressure once the slope actually failed, could allow the failure to proceed very quickly, potentially making the event dramatic to watch. Little of the failed material appears to remain in the failure scars, suggesting the sliding mass had sufficiently low friction and enough momentum to completely clear the scar. The GIF below narrates the overall process…it may load slowly.

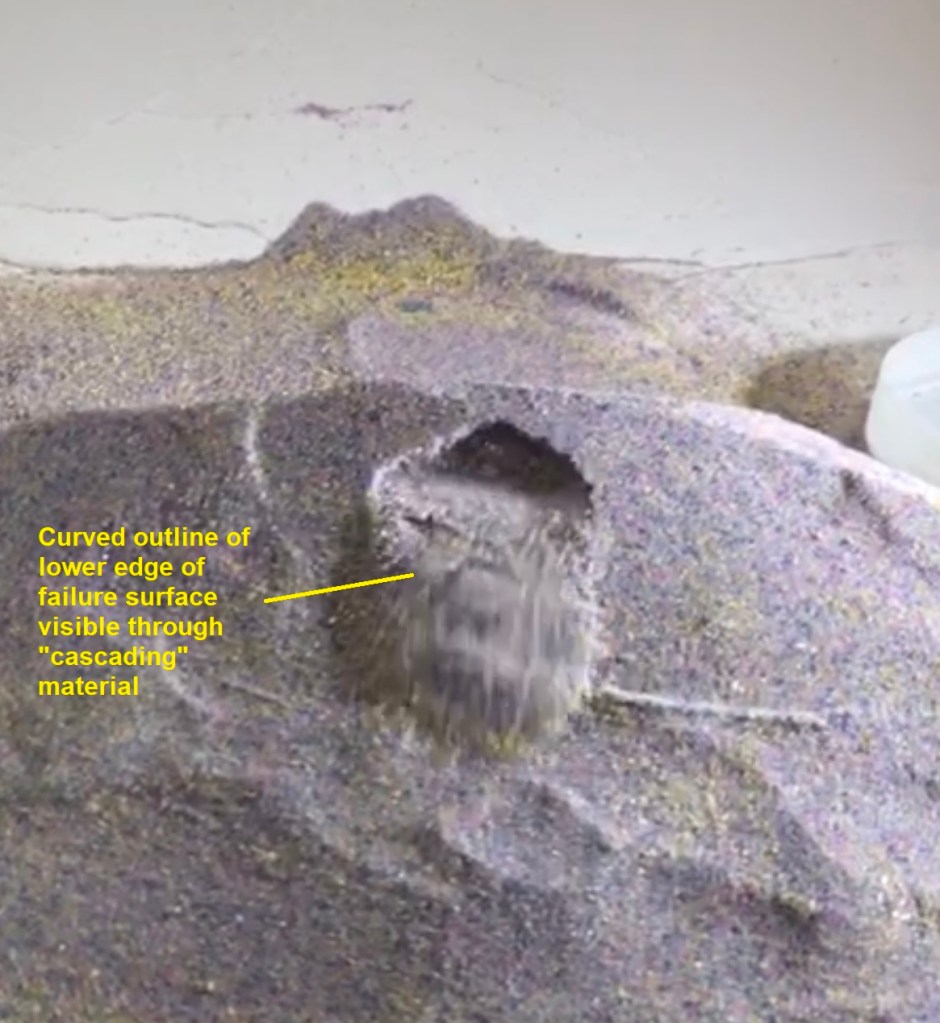

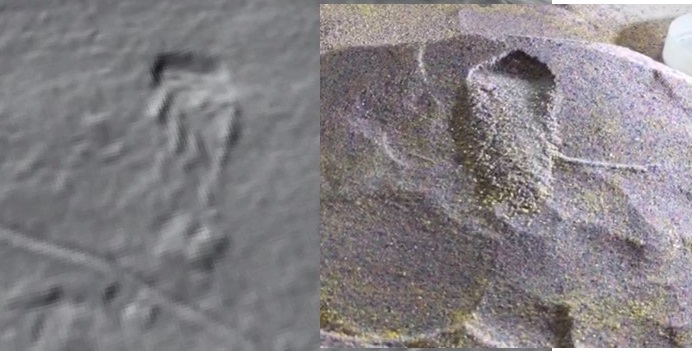

If an observer viewed this process from below, with line of sight generally parallel to the intact slope, the impression would absolutely be of outward, and possibly even upward, movement by the downslope end of the slide mass. I am a big fan of physical models, and some aspects of the blowout movement process can be captured using sandblast beads with a low-friction coating buried within stronger granular material. The beads are designed to flow from a container into a sandblasting device, so they provide a way of hinting at the weak behavior of the saturated soil. The model shown below is photographed straight-on, but the shadow produced at the toe of the soon-to-be blowout shows that it projects upward and outward from the intact slope. This will make more sense when you get to the GIF a couple images down…

The sliding material in the image above is just starting to accelerate out of the failure scar. As it picks up speed, it breaks apart while passing over the downslope lip of the scar, which is visible through the cascading material.

Now, in motion:

The weak material in this little model needs to be much weaker–this is the best that dry materials will do. Even so, the general idea–and visual impression– of an apparent burst of material out of the scar on the slope is communicated. The mass of moving material does not remain intact, and approaches a flow-like movement before rapidly losing momentum. Details like the thin trails of debris leading from the edge of the failure scar are commonly observed on the real failures.

Soil pore water is certainly the key player in the localized occurrence and behavior of the real slides, and a particular aspect of their documented behavior reflects the fluidization of the material that “blew out.” Both Eisenlohr and Hack and Goodlett (link here) noted that blowouts did not significantly damage the slopes below them, over which the material flowed. An intact block of material that fit a failure scar 50 ft x 40 ft x 10 ft (15 m x 12 m x 3 m) would, of course, have “bulldozed” vegetation out of its way, so the blowouts were apparently fluidized during movement owing to the saturation of the soil involved. The YouTube video linked below shows what this fluidization looks like. The video only captures the failure of a small block after the main event, which was probably quite impressive. Note how the small trees near the end of the video are unaffected by the flowing material, keeping in mind that they also survived the main failure (or failures). The shape of the failure surface is also visible, and is highlighted by the block’s movement.

This slide appears to be occurring in a residual soil lacking the rock fragments and boulders of the Appalachian examples. Presumably, the Appalachian examples would have produced a far-traveled sheet of fluidized, finer-grained soil like this New Zealand slide, which would have traveled beyond boulders and larger fragments contained in the colluvial soil. Like the Appalachian examples, the New Zealand slide does not significantly erode the slope below it, though there is some impact. The GIF below shows recovery of the slope over the next few years (might load slowly, etc. etc.), and gives an idea of how some Appalachian blowouts leave only a failure scar with no obvious deposit visible after a few decades.

This GIF might, to some degree, channel Hack and Goodlett’s thinking as they surveyed results of the 1949 Shenandoah Flood 6 years after the event had occurred. The non-destructiveness of the blowouts to the forest soil downslope was a point of considerable interest to them, with their report noting that only sapling trees smaller than 2 inches (5.1 cm) in diameter were knocked down by the blowout debris. Notably, the broken saplings weren’t pulled out the ground, emphasizing just how intact the land surface remained. Most of the blowouts they surveyed were 50 feet (15 m) wide, so a considerable amount of material moved over the slope without causing substantial damage.

While blowout-style slides are clearly less destructive to slopes than erosive debris flows, you still wouldn’t want to be below one when it happened. Many of the Appalachian examples mobilize large boulders within the debris sheet. Finer material, consisting of cobble-size rock fragments and soil, travels well beyond the boulders, as is visible in the Sugar Hollow, Virginia, image below. This sort of event would still be destructive if it occurred upslope of, and within reach of, buildings or infrastructure.

Blowout occurrence also appears to be less predictable than debris flows, in that blowouts develop out of hollows, on planar or convex slopes. Even so, they seem to be rare (only occurring in the most extreme rainfall events) and less mobile than debris flows, so they don’t represent a comparable threat to public safety. These slides are, however, an interesting expression of material movement, and a good example of how saturated soils can do interesting things during disturbance and failure.

“Blowout” landslides and the lidar signature of several catastrophic, mid-summer Appalachian precipitation events of the 20th century

by Philip S. Prince

All parts of the Appalachian Mountains are no stranger to episodes of localized but catastrophically extreme precipitation, with the eastern Kentucky event of July (2022) and its tragic consequences being the most recent reminder. These precipitation events, which typically occur during summer months, can deliver double-digit inches of rain (more than 25 cm) in just a few hours, with event rainfall totals sometimes exceeding 30 inches (~76 cm) in well under 24 hours. Unsurprisingly, such a quantity of rain produces significant flooding and landsliding, often in the form of fast, mobile debris flows, which present extreme risk to human life. While the landslides associated with these storms are well remembered by those who experience them, their visual record is usually eliminated in a couple of decades by the re-growth of thick vegetation. The GIF below shows how June 1995 debris flows that occurred near Graves Mill in Madison County, Virginia, are significantly less visible after 20 years. This storm produced in excess of 30 inches of rain. The GIF may load slowly…

These extreme precipitation events need to remain part of the collective societal conversation, and high-resolution lidar imagery provides an excellent way to keep their landslide record visible, regardless of vegetation. Lidar imagery also reveals unique and more subtle details of how mountain slopes respond to such extreme rainfall, including an unusual type of landslide that appears to occur in only the most exceptional rainfall events: the “blowout.” This style of slope failure was first described Pennsylvania in 1952 in association with a July 1942 storm, and several examples of it are unmistakably present on the Transylvania County, North Carolina, slope shown below. The large scar just left of the center of the image is about 100 ft (30 m) across.

When I started mapping landslides in Transylvania County in early 2022, I had no idea why “blowout” was a choice for landslide type within our mapping software. I did, however, have a sense that the slides shown in the lidar image above were different from any features I had yet encountered in the field. They resembled debris flows, but did not create an erosive track. Scars left by the slides tended to have flat bottoms, suggesting rotational failure, and were round or elliptical in outline with smoothly curved failure surfaces. Many of the slides were particularly interesting to view with lidar because of the streams of debris they produced, which would have traveled as an overland “sheet” of soil, cobbles, and boulders at the time of failure. The view below is looking right-to-left along the slope shown above. This perspective highlights the shape of the failure scars nicely.

ALC Principal Geologist Jennifer Bauer suggested that these Transylvania slides were “blowouts” after examining a few in the field and reflecting on her experiences mapping in Watauga County, North Carolina. Watauga County experienced a catastrophic precipitation event in 1940 that produced slides recorded as blowouts, and a bit of lidar comparison made clear that the unusual Transylvania County slides were definitely 1940 Watauga-style blowout features. Some Watauga examples are shown in the images below.

Significantly, the Transylvania slides were themselves located in an area struck by the region’s “storm of record” in July 1916 (and possibly the 1940 storm as well), so the extreme precipitation context also fit the Watauga analog setting nicely.

The 1916/1940 events appear to have generated no shortage of blowouts of various size in central Transylvania County, though many occurred in areas that were probably sparsely inhabited or uninhabited at the time. The example below is an exception, and the current property owner shared his family’s recollection of the failure during the 1916 storm. An interesting detail of the story is that material from the blowout travelled all the way to the French Broad River, but left no eroded track on the landscape (more on this in an upcoming post). This “trackless debris flow” description seems apt for the blowout landslide style in general.

I was interested in the origin of the actual “blowout” terminology, which was first used by Eisenlohr (1952) to describe landslides that occurred near Port Allegany, Pennsylvania, during a July 1942 storm (click here for link). Eisenlohr explicitly states that the term (originally written as “blow-out”) was selected “for want of a better expression.” Note that the “blow-outs” were specifically associated with areas receiving over 10 inches (25.4 cm) of rainfall, consistent with the events producing blowouts in western North Carolina.

I thought this Pennsylvania “type locality” was worth a lidar look, and, indeed, it revealed characteristic blowouts despite hosting highly distinct bedrock geology and slope geometry. The next three images show examples from Port Allegany’s immediate surroundings.

So, are blowouts a hallmark feature of extreme precipitation events, at least in Appalachia? The 20th century has seen several notable “double-digit” rain events throughout the Appalachian range, and the most extreme ones all produced blowouts that are readily visible with good lidar imagery. Hack and Goodlett (1960) (linked here) used the term to describe features formed on Shenandoah Mountain in Augusta County, Virginia, in a June, 1949, extreme rainfall event, and they are clearly blowouts, as the term was previously–and still is–used. Several are visible in the foreground below, with many more highlighted in the background.

The June 1995 Madison County, Virginia, event (link here) also produced blowouts amongst the numerous debris flows. A notable example is shown below–this failure is located on a surprisingly modest and convex slope, where soil pore water pressure might not be expected to reach extreme highs.

The same system that produced the 1995 Madison County storm also produced localized extreme events further south. The headwaters area of the Moorman’s River above Sugar Hollow Reservoir in Albemarle County, Virginia, was particularly hard-hit. Numerous blowouts are visible in lidar imagery of slopes in this area. The first image below labels several; the second image is a detail of the 75-ft wide feature. The third image shows an interesting cluster of smaller blowouts…note the thin translational slide next to the “8 m” label.

In areas of Blue Ridge Virginia devastated by the remnants of Hurricane Camille (link here) in August 1969, blowouts are visible amongst the almost unbelievably widespread debris flow scars. The significant human toll associated with debris flows from this storm renders mention of the less hazardous blowout-style failures a bit out of context, but blowouts are present (as expected) given the magnitude of precipitation experienced during this landmark event. The image below shows a few blowouts, but the debris flow features visible in the foreground (the longer tracks; not the elliptical blowout) are certainly the most significant aspect of the event.

In September 2004, the remnants of Hurricane Ivan (link here) produced at least one blowout failure near Nickajack Creek in Macon County, North Carolina. As with the Camille event, this tiny failure is overshadowed by the deadly debris flow on nearby Peeks Creek, but its presence likely offers good indication of precipitation intensity associated with Ivan’s remnants.

Blowouts appear to have a definite association with very extreme rainfall, and (in Appalachia at least) they may only occur in precipitation events that exceed totals necessary to cause debris flows. Most of the events referenced here involved extreme rainfall onto already saturated soils. Many of the blowouts observed in the field or with lidar imagery developed on planar or convex slopes, a distinction from typical debris flow initiation in concave hollows on mountainsides. This distribution is visible below, in a slightly-rotated view of the earlier Sugar Hollow image.

All of the blowouts visited in the field occurred in colluvial soils, and blowouts observed with lidar imagery all occur in locations likely underlain by colluvium. Many of the features visited were wet during dry weather, suggesting details of shallow groundwater movement, soil type, bedrock depth, and localized pore pressure increases during extreme rainfall all come together to make blowouts happen in specific locations. Their tendency to cluster or align along bedrock boundaries beneath soil supports this idea, which was suggested by Eisenlohr and Hack and Goodlett based on observation in their generally flat-lying sedimentary rock study areas. The second Sugar Hollow image (4 images up from above) shows a nice example of clustered failures. While Sugar Hollow is underlain by low-grade metamorphic rock, mechanical distinctions and intersecting joint sets are very much present and influence shallow groundwater movement.

A particularly interesting blowout detail is that they tend to look the same, regardless of area geology, elevation, relief, or latitude. A Port Allegany, Pennsylvania, blowout looks just like many Transylvania County, North Carolina, features, despite the areas being over 500 miles (~800 km) apart and being underlain by nearly flat-lying sedimentary rock and intensely deformed metamorphic rock, respectively.

All of the examples in this post differ in terms of bedrock (among other details), but the failures are remarkably similar in appearance. Presumably this detail has been adequately illustrated by this point…

The association of blowouts with extreme rainfall might make older features an interesting source of information about climate (or specific weather event) history in an area, but the features don’t seem to preserve well in the landscape. The only “older,” or at least slightly less-fresh looking blowouts I have seen are near Hiawassee, Georgia, on colluvial slopes along Ramey Mountain. They lack the crisp features seen in the examples already shown, but the distinct failure shape and debris sheet are definitely present.

Do the Hiawassee feature and its neighbors record an older extreme precipitation event? Material entrained in the debris sheet might offer an answer, but using these features to date older events would likely be challenging. They do, however, provide a glimpse into unique slope behavior during the most extreme storms, and might end up occurring more frequently in coming decades…