Landslides (and particularly debris flows) aren’t a daily occurrence in western North Carolina, so knowledge of the landslide risk of a specific property may not always seem important. A few years ago, ALC advised a client against purchase of a high-risk property located in an area that, at the time, seemed quite safe and desirable for a mountain home. The risk potential of the property turned into devastating reality during Helene, and a significant loss was avoided thanks to the pre-purchase site evaluation and subsequent decision to buy and build elsewhere. The locations and images of the impacted property are described in this post with the client’s permission. Her experience is noted in a Garden and Gun article linked here.

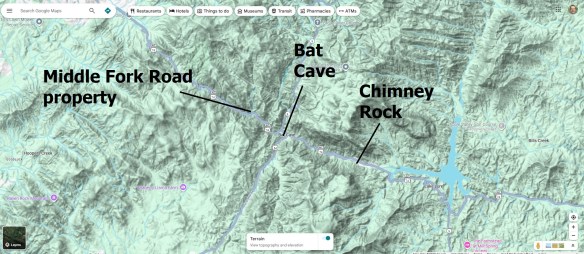

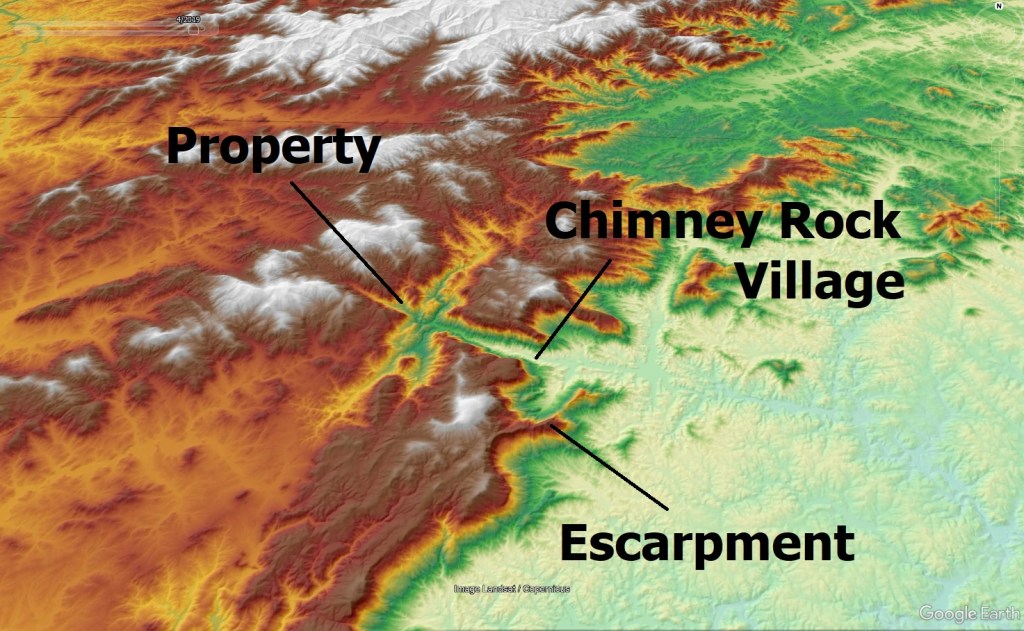

The impacted property is located immediately adjacent to Middle Fork, a tributary to Hickory Creek just upstream of Bat Cave, North Carolina.

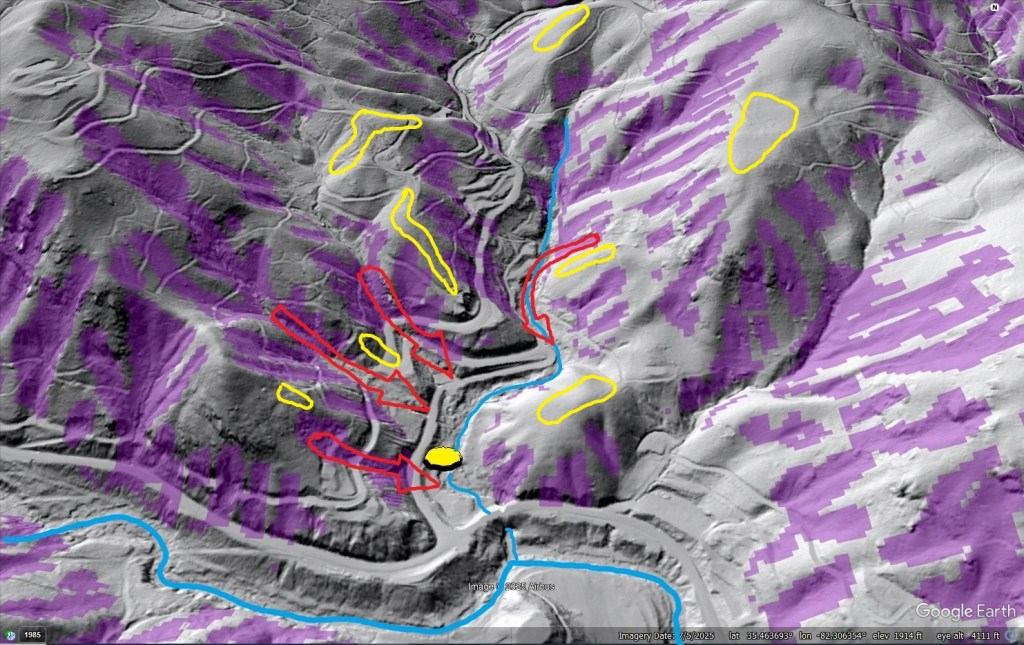

The location raised immediate concern during ALC’s evaluation because of the property’s potential to be impacted by both debris flows and flash flooding. A known debris flow occurred just northwest of the property (yellow outline below), nearly reaching it. The property itself is located in mapped landslide deposits (orange outline), and numerous potential debris flow initiation areas (purple) were identified upstream of the location by ALC’s Susceptibility Model.

Debris flows are exceedingly mobile and can transition into more flood-like features as they travel down streams and mix with runoff, extending considerably the potential reach of debris flow hazards from potential source areas. Even without landslides that develop into debris flows, the potential for flash flood impact on the property was significant. The property is located on a streambank in a small gorge in the Blue Ridge Escarpment Zone, where topography can force air masses to rise and produce extreme localized rainfall.

This rainfall, combined with the steep topography, quickly makes normally tiny streams very dangerous. The location in question would, eventually, see the effects of an extreme storm event. The only question was when this would happen.

ALC recommended that the client seek another property for house construction. The streamside, off-the-beaten-path location was indeed desirable, but the potential for severe impact across the entirety of the property was too great. While the Middle Fork property could have daytime recreational value, living (particularly sleeping) there and investing in a structure on the site was too great a risk. In September 2024, Helene showed just what that risk looked like. The top image shows the site before Helene; the bottom image is the same view after the storm.

Both significant debris flow events and record flooding affected Middle Fork, scouring the property and leaving enormous piles of debris behind, including huge, mature trees mobilized by debris flows and floodwaters. A structure on the property would have been a total loss, and anyone inside during the peak of Helene’s impacts would have faced serious injury or death. The GIF below compares pre-Helene, 2023 imagery to post-Helene imagery. The property location is shown by the large yellow arrow.

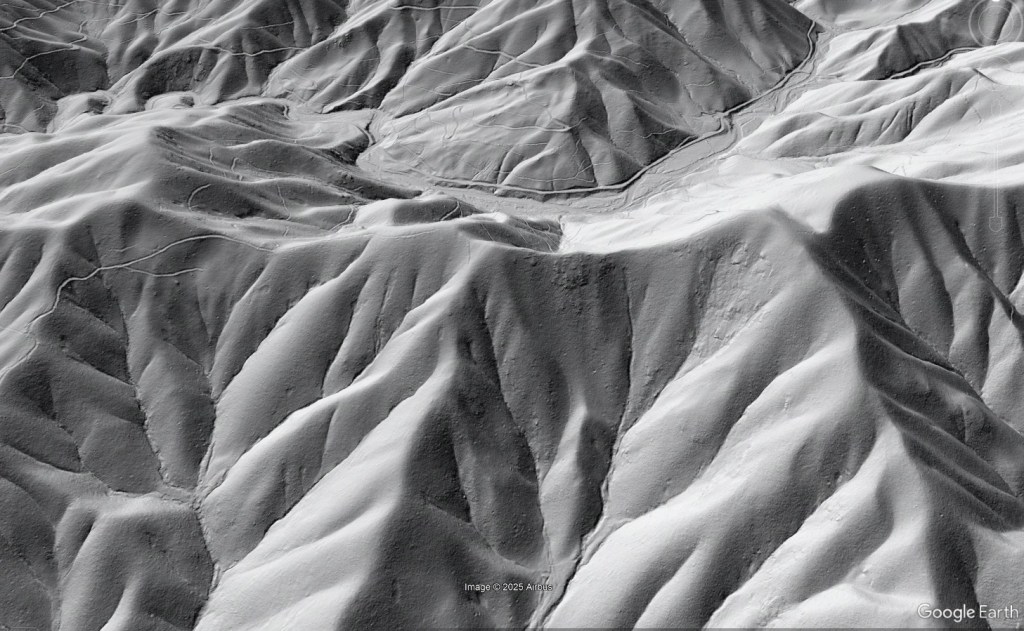

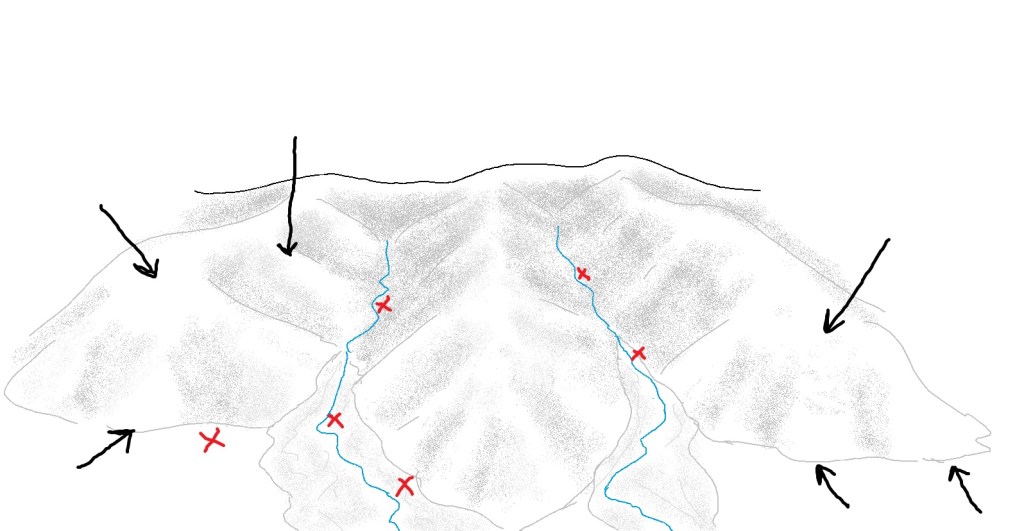

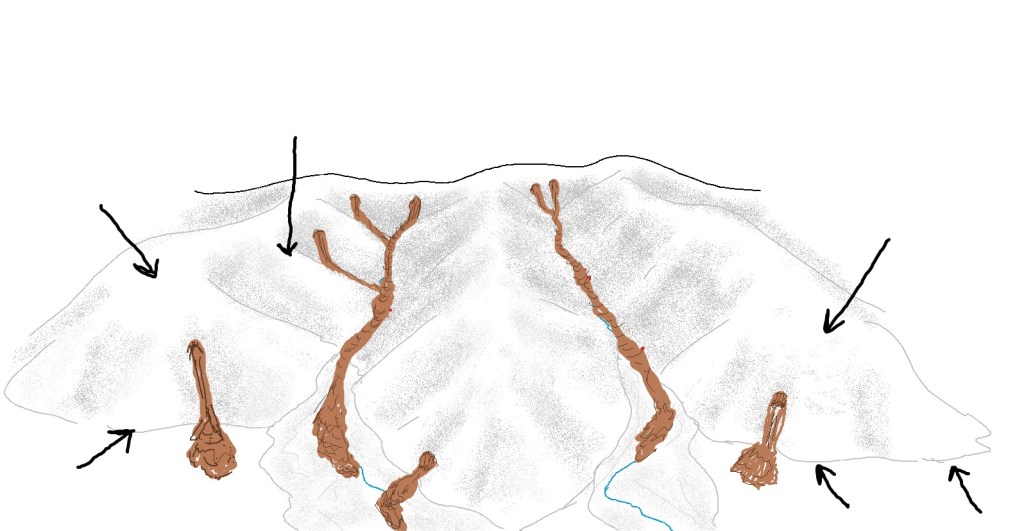

Fortunately, the client heeded ALC’s recommendation and purchased well-situated property in Yancey County, which avoided damage due to its position within the landscape despite Helene’s catastrophic impacts in Yancey. The hazard potential on both the selected Yancey property and the Middle Fork property were evaluated remotely–simply looking at detailed topographic maps, lidar imagery, and records of past debris flow events painted a clear picture to geologists with years of experience in the region. In this case, the return on investment in the evaluation was quite significant, with the client able to avoid a major loss and instead devote resources towards a property in a more stable and resilient location. The fundamental concept behind this type of evaluation is being able to read the landscape shape and history and visualize impact potential. The images below illustrate the concept. Black arrows show locations where convex slopes (and often elevation) steer debris flow and flood hazard away; red X’s are in areas to which debris flow and flood hazards are directed by landscape shape.

Landslide risk evaluations aren’t meant to show that entire regions are unsafe for building and living. Because debris flows and floods follow the terrain as fluids (water and liquefied soil both run downhill), their potential impact zones are limited. Even along Middle Fork, numerous safe and livable areas exist along convex portions of the landscape that shed flowing material instead of focusing it. Yellow outlines in the image below show examples of these areas–in this topography, they are noticeably on ridge tops and “noses” of slopes. That said, road networks to access those safe areas are still vulnerable, and anyone choosing to live in them should be aware that access may be difficult or impossible after a major event. Even areas with landslide and flood hazard have conservation and recreation potential, though they should not be disturbed by development and must be avoided during hazardous weather.

Interestingly, the Garden and Gun article inadvertently showcases another notable Helene event: the Celo Knob debris flow, which might have left the largest single scar (in terms of surface area) of any debris flow during the storm. The scar is visible in the background of the image below, which is from the article.

The clearly visible scar is 330 feet wide and 700 feet long from head to toe. The flow carved a nearly 5,000 foot long track down the mountain before running out of energy. The house visible near the terminus of the debris flow is somewhat above and away from the channel followed by the flow. It is uncertain whether the house could be impacted in a “worst case” debris flow event, or if such an event is even possible in the near future since so much material already moved. The scar of this huge debris is yet another valuable reminder of the importance of knowing what can happen under the right (or wrong!) conditions.