Before Helene’s remnants passed through western North Carolina, the boulder-strewn area in the photo above was covered with trees and buildings. A small stream flowed behind the wrecked buildings on the left of the photo. The damage seen here occurred suddenly on the morning of Friday, September 27, 2024, as a huge wave of boulders, trees, and mud surged down the small stream’s channel. This wasn’t a flash flood–it was a debris flow, a type of fast moving, fluidized landslide associated with heavy rainfall. The extent of the damage from the debris flow is visible in the before/after GIF below. The photo above was taken near the top of the GIF images, looking towards their bottom. The large building labeled above is visible near the bottom of the GIF images.

The small stream is visible trickling through the damage swath; water flooding alone from a stream this small could never approach the level of damage caused by the debris flow. Fortunately, no one was seriously injured in this particular debris flow, but many lives were lost in similar events elsewhere during Helene. Understanding these particularly dangerous landslides is a big part of storm safety in southern Appalachia. So, what are debris flows, where do they start, and what makes them so dangerous?

What are debris flows?

Debris flows are fast-moving, highly mobile, fluidized landslides transporting saturated soil, boulders, and trees downslope. They are specifically associated with saturated soil, which results from heavy rainfall in our region. Debris flows move like a liquid but contain large amounts of solid material–65% solids (rock, soil, and wood) is an average composition, with the rest of the flow volume being water mixed into the soil and rock. Often called “mudslides,” debris flows also carry large trees and boulders. Because of their solid content, debris flows are approximately twice as dense as water, so they hit with destructive force. They follow ravines and small stream channels downslope due to their fluid consistency, spreading over wider areas at the base of slopes until they lose their momentum. The sketch below gives a general idea of a debris flow’s start-to-finish journey downslope, from its beginning in a steep hollow to its damaging end on flatter ground at the base of the mountain.

Where and how do debris flows start?

Debris flows frequently start in steep hollows, or slightly concave slope areas, above the headwaters of small streams. They can also begin on road embankments, or any other landscape feature that can initiate a small landslide on steep ground. Debris flows are specifically associated with heavy precipitation and saturated ground. When a landslide starts in saturated soil, it liquefies and accelerates. When the liquefied landslide hits the saturated soil in its path, this soil liquefies as well and is added to the debris flow. Much like a snowball, debris flows accumulate more and more debris moving downslope, adding to their volume and destructive power. The GIF below shows the basic idea of debris flow initiation in an area like the one indicated by the red box in the sketch above. Note that the debris flow starts in rocky soil beneath a cliff, where rock fragments have accumulated to the point of instability. Due to saturation, once the slide starts, it liquefies, and then liquefies the soil in its path.

How do debris flows move?

Debris flows follow ravines and stream channels due to their liquefied condition, typically scouring large amounts of soil and stream sediment on their way down. Moving within the stream channel keeps the flow confined and intact. Collisions between soil and rock particles help keep the flow liquefied. A confined, thicker flow also loses less of the water trapped within it. Debris flows can move very quickly, often at speeds of 20 mph or more. They frequently run up onto the slope on the outsides of bends due to their speed. Their width greatly exceeds the width of the stream or creek whose channel they follow. The conceptual sketch below illustrates the scouring process as well as debris flow size relative to the “usual” stream in the channel, even during high water flow.

The scouring created by debris flows can be quite impressive; it greatly exceeds the potential for water erosion by small headwater streams. The picture below (taken upslope of the first photo in this post) gives an idea of what the effects of the scouring look like.

The leading edge of the debris flow contains trees and larger boulders picked up by the debris flow through its scouring action. Smaller cobbles and mud trail behind. Even small debris flows can transport surprisingly large boulders and trees due to the density of the fluidized soil (it “floats” boulders), making a debris flow strike on a structure incredibly destructive.

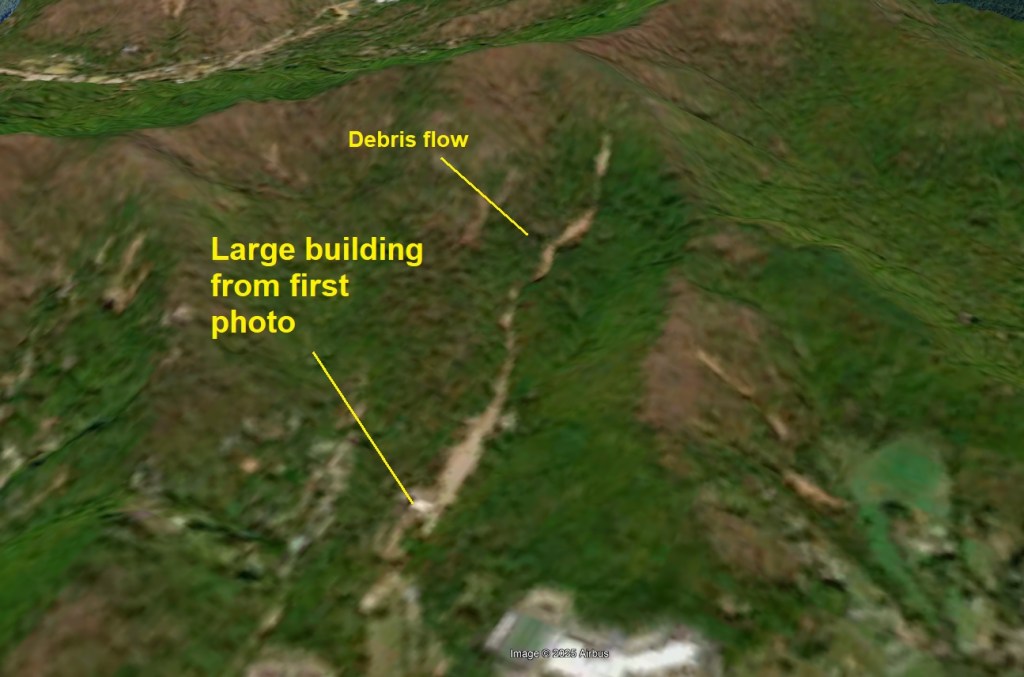

When debris flows exit tighter channels or ravines onto flatter ground, they often spread out, but remain mobile and destructive for some distance. In western North Carolina, many tight stream channels open onto flatter areas at the base of the steep slope. These flatter areas are older, accumulated debris flow deposits. The GIF below shows debris flows exiting a stream valley and spreading onto a flat deposit area, where buildings are destroyed. Though an unpleasant thought, this sequence of events played out many times during Helene (as well as during many other storms in our region’s history). The satellite photo below the GIF shows a bird’s eye view of the debris flow where the first photo in the post was taken.

Debris flow deposits are an indicator that an area can experience debris flows and should be developed cautiously, if at all. This often seems counterintuitive, as the flatter slopes suggest safety from landslides. In reality, these flat deposit areas are a main indicator of possible debris flow hazard. People already living in such areas should be aware of the hazard during heavy rainfall. In southern Appalachia, about 5 inches of rain over 24 hours produces conditions necessary to make debris flows possible.

This is the first post in a series of Helene-related posts discussing landslide events during the storm. Posts will be a combination of remote sensing interpretation and first-hand, on-the-ground experience. Our goal is to increase understanding of what happened during this event and help folks plan for future hazard.

Additional discussion of how debris flows fluidize can be found in this video. It’s an interesting process that isn’t fully understood, but the basics are outlined here in greater detail.